By Pati Ruiz and Amar Abbott

The 2020-2021 school year is underway in the U.S. and for many students, that means using edtech tools in a fully online or blended learning environment. As educators, it is our responsibility to consider how students are using edtech tools and what the unanticipated consequences of using these tools might be. Before introducing edtech tools to students, administrators should spend time considering a range of tools to meet the needs of their students and teachers. In a recent blog post, Mary Beth Hertz described the opportunities for anti-racist work in the consideration and selection of the tools students use for learning. Hertz identified a series of questions educators can ask about the tools they will adopt to make sure those tools are serving the best interest of all of their students. Two of the questions in Hertz’s list ask us to consider data and algorithms. In this post, we focus on these two questions and Hertz’s call to “pause and reflect and raise our expectations for the edtech companies with which we work while also thinking critically about how we leverage technology in the classroom as it relates to our students of color.” The two questions are:

- How does the company handle student data? and,

- Has the company tested its algorithms or other automated processes for racial biases?

To help us better understand the issues around these two questions, we will discuss the work of two researchers: Dr. Safiya Noble and Dr. Ruha Benjamin. This post expands on our previous post about Dr. Noble’s keynote address — The Problems and Perils of Harnessing Big Data for Equity & Justice — and her book, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. Here, we also introduce the work of Dr. Ruha Benjamin, and specifically the ideas described in her recent book Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code.

Student Data

In order to understand how companies handle student data, we need to first consider the concept of data. Data are characteristics or information that are collected in a manner capable of being communicated or manipulated by some process (Wiktionary, 2020). In Dr. Noble’s keynote speech, she discusses the social construction of data and the importance of paying attention to the assumptions that are made about the characterization of data that are being collected. In her book, Dr. Noble shows how Google’s search engine perpetuates harmful stereotypes about Black women and girls in particular. Dr. Benjamin describes the data justice issues we are dealing with today as ones that come from a long history of systemic injustice in which those in power have used data to disenfranchise Black people. In her chapter titled Retooling Solidarity, Reimagining Justice, Dr. Benjamin (2019) encourages us to “question, which humans are prioritized in the process” (p. 174) of design and data collection. With edtech tools, the humans who are prioritized in the process are teachers and administrators, they are the “clients.” We need to consider and prioritize the affected population, students.

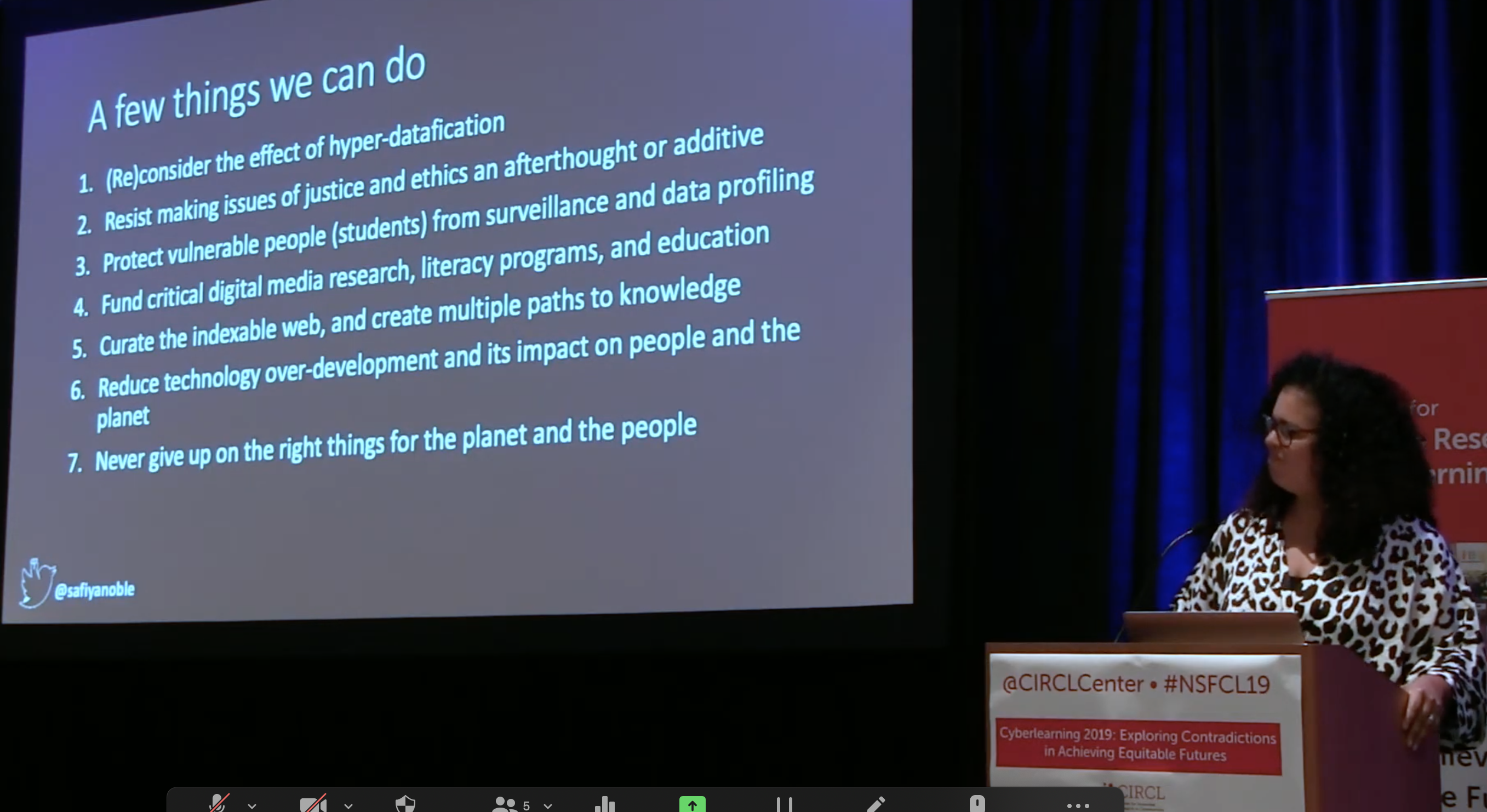

When it comes to the collection and use of educational data and interventions for education, there is much work to be done to counteract coded inequities of the “techno status quo.” In her keynote, Dr. Noble offered a list of suggestions for interventions including:

- Resist making issues of justice and ethics an afterthought or additive

- Protect vulnerable people (students) from surveillance and data profiling

Center Issues of Justice and Ethics

As described by Tawana Petty in the recent Wired article Defending Black Lives Means Banning Facial Recognition, Black communities want to be seen and not watched. The author writes:

“Simply increasing lighting in public spaces has been proven to increase safety for a much lower cost, without racial bias, and without jeopardizing the liberties of residents.”

What is the equivalent of increasing light in education spaces? What steps are being taken to protect students from surveillance and data profiling? How are teachers and students trained on the digital tools they are being asked to use? How are companies asked to be responsible about the kinds of data they collect?

Schools have legal mandates meant to protect students’ rights, such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) in the U.S. and other policies that protect student confidentiality regarding medical and student educational records. Although a lot of forethought has gone into protecting students’ confidentiality, has the same critical foresight implemented when purchasing hardware and software?

In Dr. Noble’s keynote speech, she described the tracking of students on some university campuses through the digital devices they connect to campus Internet or services (like a Library or Learning Management System). The reasoning behind tracking students is to allocate university resources effectively to help the student be successful. However, in this article, Drew Harwell writes about the complex ethical issues regarding students being digitally tracked and an institutions’ obligation to keep students’ data private. So, before software or hardware is used or purchased, privacy and ethics issues must be discussed and addressed. Special energy needs to be dedicated to uncovering any potential “unanticipated” consequences of the technologies as well. After all, without the proper vetting, a bad decision could harm students.

Protect Vulnerable Students

Protecting vulnerable students includes being able to answer Hertz’s question: “Has the company tested its algorithms or other automated processes for racial biases?” But, even when the company has tested its algorithms and automated processes, there is often still work to be done because “unanticipated” results continue to happen. A Twitter spokesperson Liz Kelley recently posted a tweet saying: “thanks to everyone who raised this. we tested for bias before shipping the model and didn’t find evidence of racial or gender bias in our testing, but it’s clear that we’ve got more analysis to do.”

She was responding to the experiment shown below where user @bascule posted: “Trying a horrible experiment…Which will the Twitter algorithm pick: Mitch McConnell or Barack Obama?”

Twitter’s machine learning algorithm chose to center the white face instead of the black face when presented with where the white profile picture was shown on top, white space in between, followed by the black profile picture. But it did the same when the black profile picture was shown on top, white space in between, followed by the white profile picture.

As we can see, the selection and use of tools for learning is complicated and requires balancing many factors. As CIRCL Educators we hope to provide some guidance to ensure the safety of students, families, and their teachers. Additionally, we are working to demystify data, algorithms, and AI for educators and their students. This work is similar to the work being done by public interest technologists in the communities and organizations described by both Noble and Benjamin. We don’t have all of the answers, but these topics are ones that we will continue to discuss and write about. Please share your thoughts with us by tweeting @CIRCLEducators.

References

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

data. (2020, August 12). Wiktionary, The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 15:31, August 26, 2020 from https://en.wiktionary.org/w/index.php?title=data&oldid=60057733.

Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press.