Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages

by Sarah Hampton and Dr. Dalila Dragnić-Cindrić

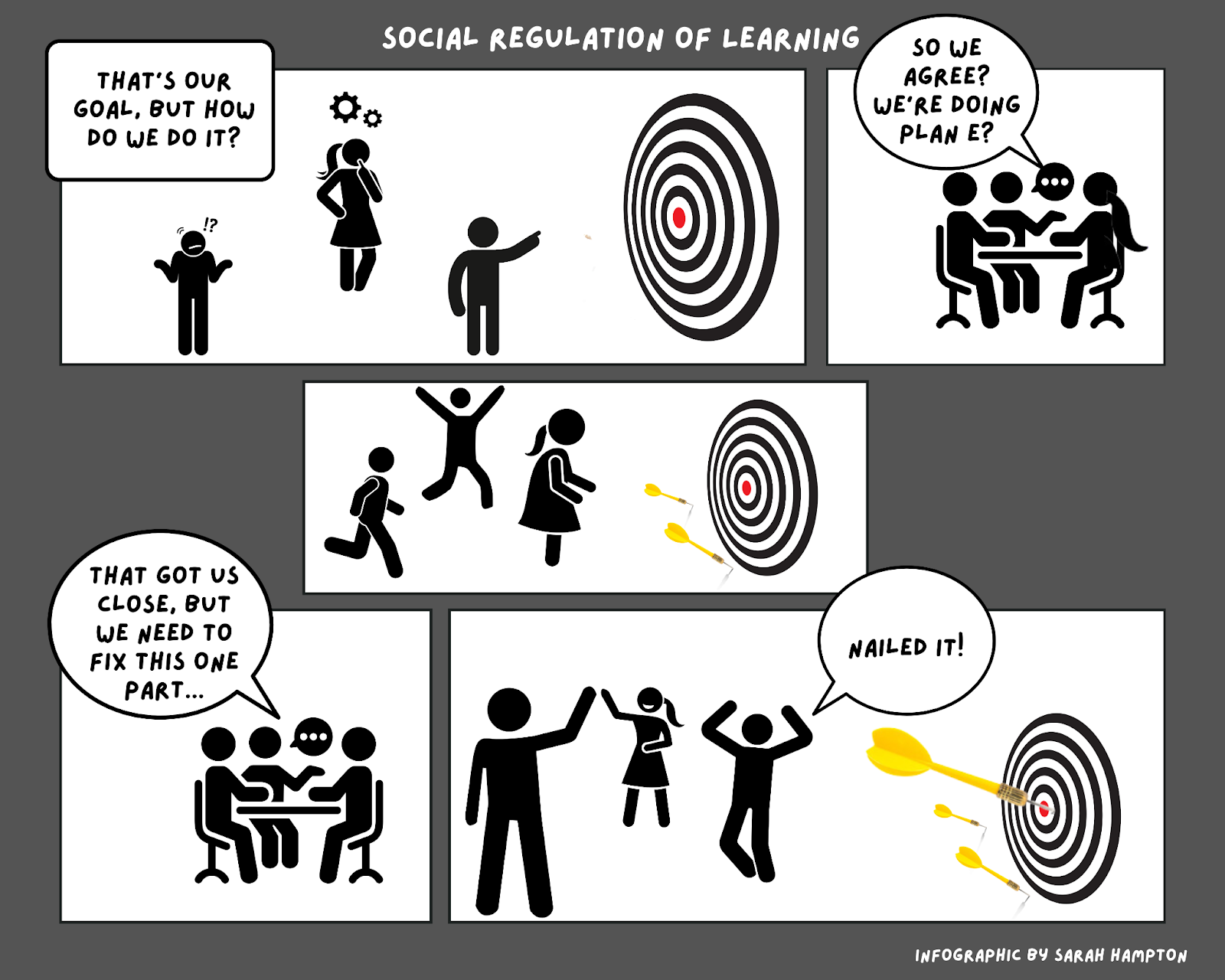

In our two previous blog posts, we talked about students’ individual self-regulated learning (SRL), group-level, social regulation of learning (SoRL), and why it’s important to explicitly teach both alongside our content (Hampton & Dragnić-Cindrić, 2023a, 2023b). The link between students’ effective self-regulated learning and successful academic and life outcomes has been well documented (Dent & Koenka, 2016). If that’s the case, and if we know the benefits, why don’t more teachers focus on teaching it?

In this post, we will explore some of the barriers and possible solutions for teaching regulation of learning that we have seen in K-12 and higher education classrooms. Importantly, some of the barriers that surfaced during our conversations are within a teacher’s control, and others are not (e.g., district or state policies). In the spirit of teacher empowerment, this post focuses on the barriers and solutions within teachers’ control.

Barrier 1: Comprehensive instruction of SRL and or SoRL requires the teacher to give up control, an uncomfortable idea for many of us.

Suggested Solution: Gradually but steadily release control of learning to the students, making them responsible for their own learning.

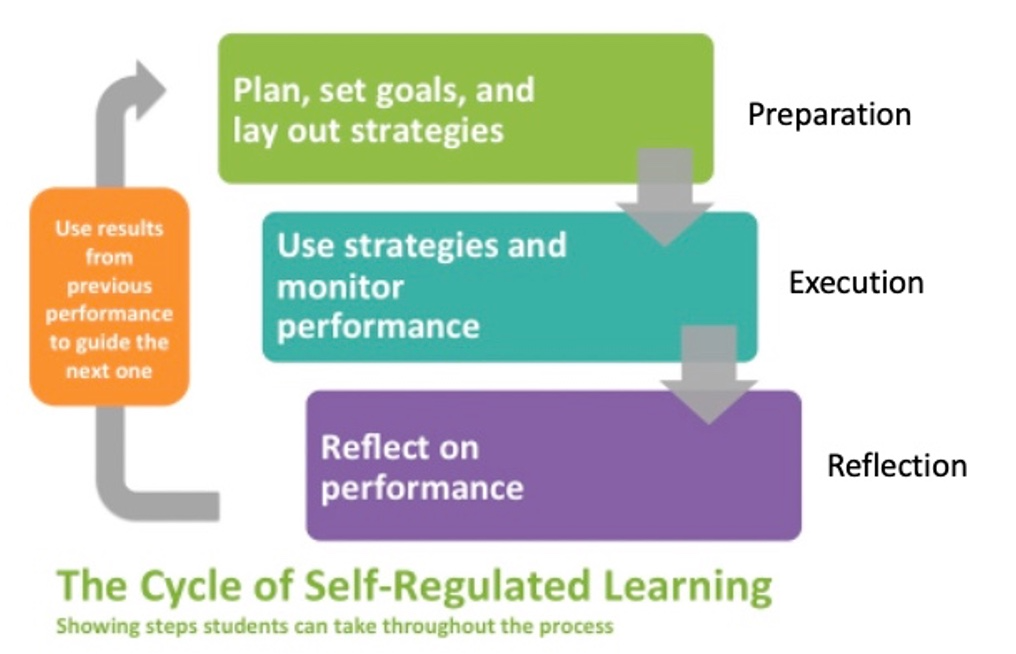

Elaboration: If we want students to take more responsibility for their own learning, then we must give responsibility back to them. Doing so gradually but steadily can help teachers overcome their own discomfort with releasing control as well as ease students into new, more active roles in their own learning.

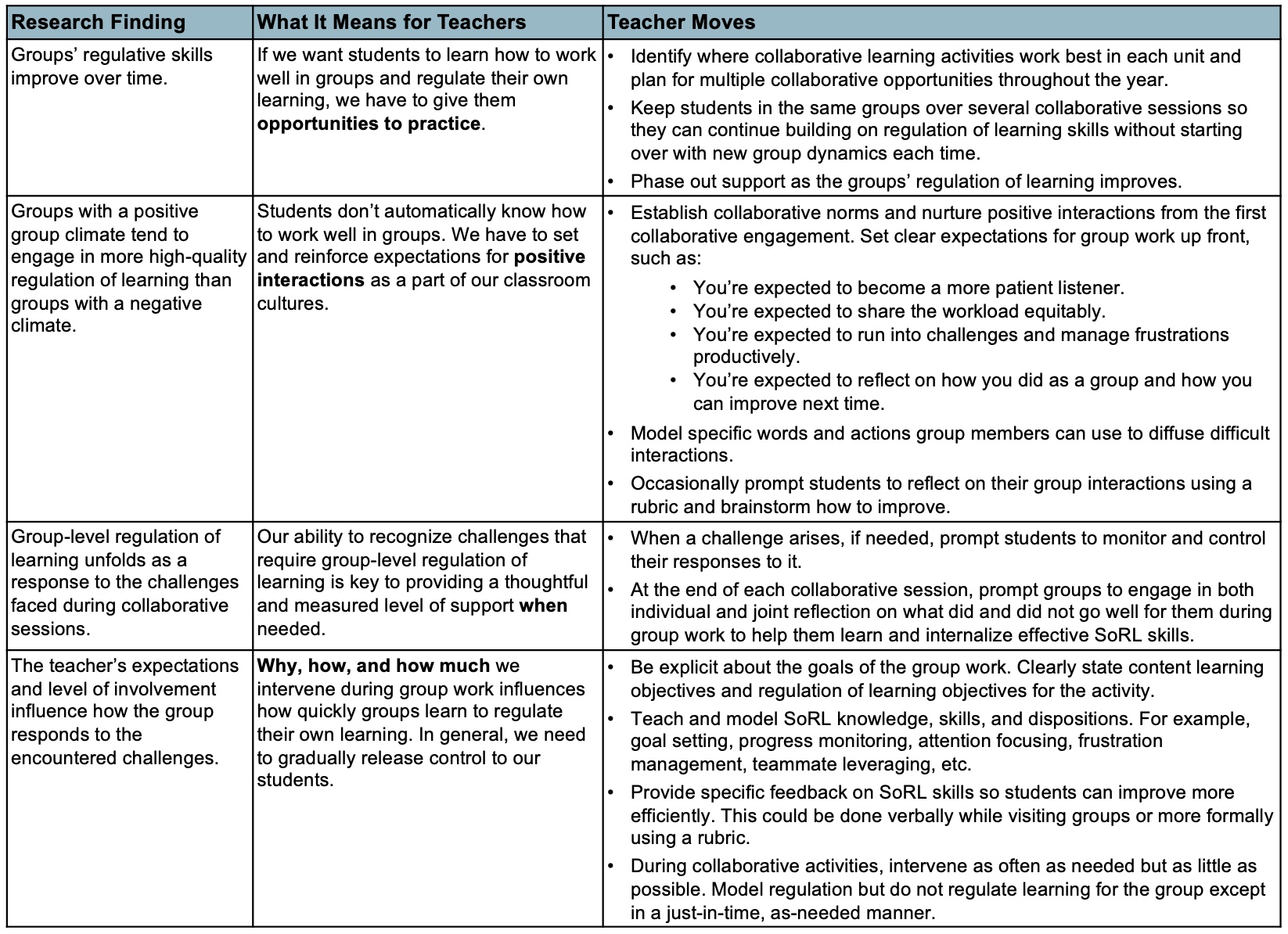

In a recent study conducted in high school physics classrooms, Dalila and colleagues showed that the level of teachers’ control over collaborative groups’ dialogues impacted groups’ SoRL. Students in groups in which the teacher controlled the conversation engaged in less conversation with each other and enacted less SoRL (Dragnić-Cindrić et al., 2023).

For Sarah, our conversation about this study led to a somewhat sobering realization. As a reflective practitioner, she said, “I realized that I had been robbing my students of taking more responsibility for their learning because I was holding onto so much of it. In an effort to maximize our learning minutes, head off classroom disruptions at the pass, and ensure successful learning outcomes, I have hoarded control of my students’ learning experiences.”

If we want students to take more ownership, we must shift more control over learning back to them. Gradual release of control means providing more support and guidance at the beginning, then fading the support as students demonstrate increased capability to manage their own learning. During our conversations on this topic, Sarah said her “aha” moment came when Dalila pointed out that regulation happens whether a teacher acknowledges it or not. “You’re modeling regulation whether you’re intentional about it or not. You’re either modeling good examples or bad examples. It’s about taking advantage of the opportunity to help students learn how to regulate their learning individually and with others.”

That leads us to the next barrier…

Barrier 2: Teachers may not be sure how to teach regulation of learning.

Suggested Solution: To teach regulation of learning, include both modeling and direct instruction of regulation of learning.

Elaboration: As teachers, we have made a career in education and are most likely effective at regulating our own learning. We have probably automated many regulation strategies and don’t even need to think about them, which can make it difficult to understand the perspective of students who find learning how to learn challenging. Because we haven’t had to explicitly think about regulation to navigate learning challenges in our own lives, we may not know how to model and explicitly articulate learning strategies to our students.

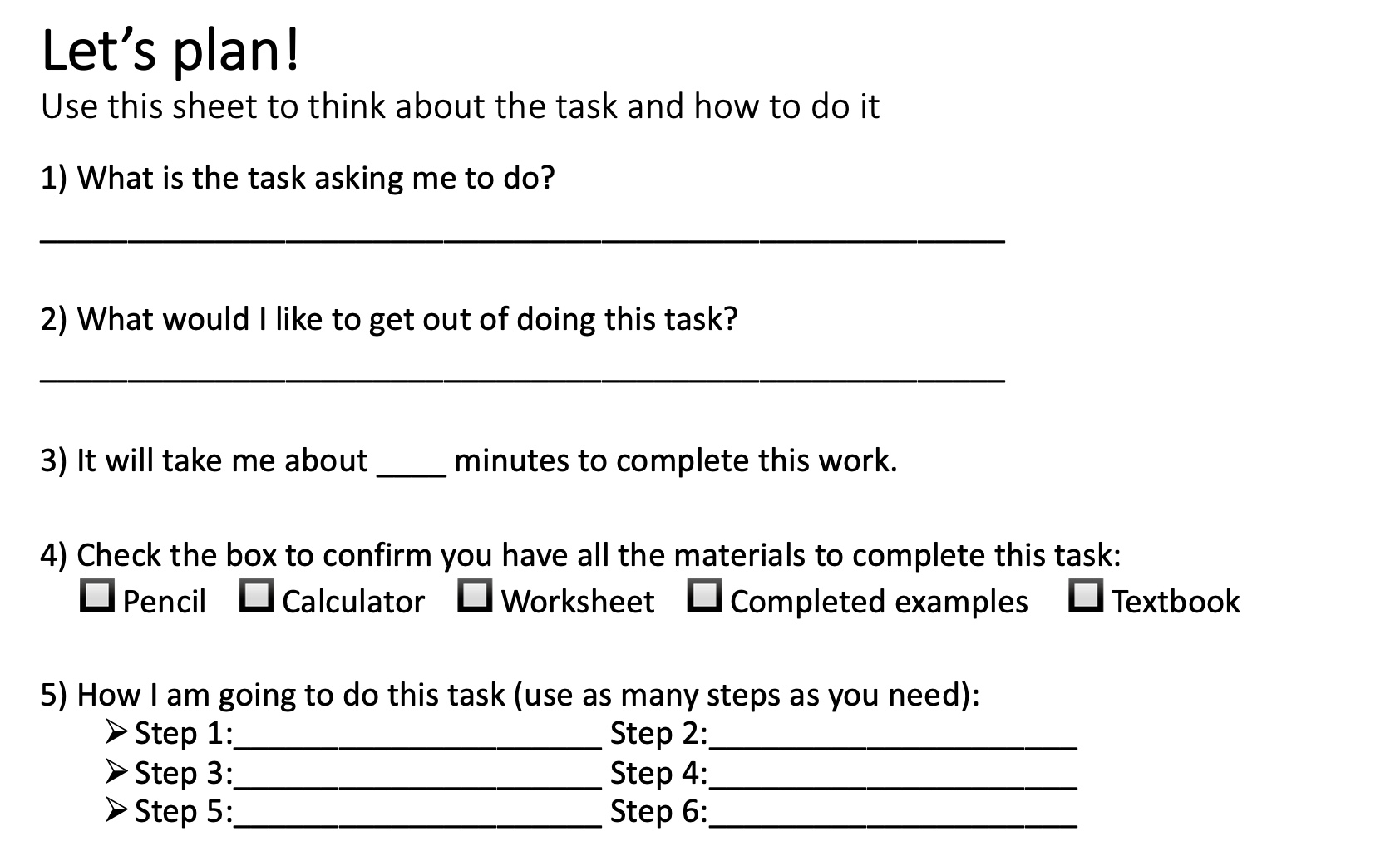

Additionally, most teacher preparation programs do not include courses on how to teach regulation of learning. We also recognize that teachers with many demands on their time don’t have the luxury of independently learning about best practices for teaching regulation and developing worksheets, prompts, reflections, etc., to help their students with regulation of learning. Still, there are some steps that can be taken to improve students’ regulation of learning through modeling and direct instruction (Paris & Paris, 2001).

- Reflect on your own learning strategies and take time to model them for your students. Narrate your own thought processes and explain how you approach and solve problems. Learn more about regulation of learning and how to teach it. We gave a brief overview in the first post of the series, but we have included more teacher-friendly resources in the Additional Resources section below. For a self-paced professional learning experience, you might like the “Self-regulation professional development module” by the Students at the Center Hub.

- Explicitly teach students effective regulation of learning and learning strategies you’re already familiar with, such as:

- Modify your learning environment and structure study time: Studying is more effective if you eliminate distractions and study in short time intervals followed by brief breaks. Put your phone away and engage in a focused 15-minute study session followed by a 5-minute break (Yes, this is the time to check that phone!)

- Summarize text and tell someone about it: When studying new material, an effective approach is to read the text and then write a summary of the main points or tell someone else, a friend or a family member, about it. Go into details as much as you can. If there are things you cannot recall, that’s a sign you might want to read that part again. Many students rely exclusively on text highlighting and re-reading. These strategies are ineffective because they create “illusions of knowing,” a false sense that you have learned the material.

- Quiz yourself to memorize new words or concepts: In subjects where memorizing content is needed (e.g., studying vocabulary), quizzing works! Quiz yourself and ask others to quiz you.

- Seek help when you get stuck: It is okay to ask for help, and smart students do! If you are stuck, ask others to explain how they approach similar problems. Show your teacher your work and walk them through it — they will be happy to help you identify the rough spots and help you work through them.

We provide links to the additional learning strategy resources below.

Barrier 3: From a short-term perspective, teaching regulation of learning feels like a less valuable use of time than teaching content.

Suggested Solution: Embrace teaching regulation of learning as an inextricable part of teaching your content’s process standards. In other words, part of the standards we’re expected to teach requires students to engage in regulation of learning (see examples below).

Elaboration: Regulation of learning isn’t directly assessed, so when it comes to spending 10 minutes of class time, teachers are likely to choose learning content over learning how to learn. However, hyperfocusing on content standards over process standards is more short-sighted than short-term. The research suggests that teaching regulation will pay content learning dividends in a single school year (Dignath & Büttner, 2008). Beyond that, learning how to navigate challenges and find a way to learn alone and together will benefit learners their entire lives.

Many school districts are adopting big-picture mission statements and portraits of a graduate. Most have a line about creating self-sufficient lifelong learners. Teaching regulation of learning is a critically important way to spend your class time. Justify that time (to yourself and others!) using your existing state and national standards and school, district, and/or state mission statements. Here are some examples:

The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) problem-solving process standards call for teachers to:

The National Council for Teachers of English calls for students to:

The National Science Teaching Association (NSTA) emphasizes that:

North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s “A Portrait of a Graduate” emphasizes that in addition to academic content, schools must be more intentional about fostering durable skills critical for students’ success, including learner’s mindset, personal responsibility, and collaboration.

These are a few of the challenges we have identified. What other barriers prevent you or your colleagues from teaching regulation of learning? How have you navigated these challenges in your classroom? We would love to hear your thoughts — tweet us at @EducatorCIRCLS!

References

Dent, A.L., & Koenka, A.C. (2016). The Relation Between Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement Across Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Dignath, C. & Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacognition and Learning, 3, 231–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x.

Dragnić-Cindrić, D., Lobczowski, N. G., Greene, J. A., & Murphy, P. K. (2023). Exploring the teacher’s role in discourse and social regulation of learning: Insights from collaborative sessions in high-school physics classrooms. Cognition and Instruction, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2023.2266847

Hampton S., & Dragnić-Cindrić, D. (2023a). Regulation of learning: What is it, and why is it important? Center for Integrative Research in Computing and Learning Sciences.

Hampton S., & Dragnić-Cindrić, D. (2023b). Social Regulation of Learning and Insights for Educators. Center for Integrative Research in Computing and Learning Sciences.

North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. (n.d.). Portrait of a graduate. https://www.dpi.nc.gov/districts-schools/operation-polaris/portrait-graduate#Tab-DurableSkills-4800

Paris, S. G., & Paris, A. H. (2001). Classroom applications of research on self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 36(2), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3602_4

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation grant number 2101341 and grant number 2021159. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Additional Resources:

Elaboration | How Expanding On Ideas Increase Outcomes | Science of Learning Series

Interleaving | Mixed up Practice | Science of Learning Series

Self-regulated learning: The technique smart students use.

Spacing | Revisit Material To Boost Outcomes | Science of Learning Series

Teacher Support of Co- and Socially-Shared Regulation of Learning in Middle School Mathematics Classrooms