by Kip Glazer Ed.D.

Kip Glazer is the principal at San Marcos High School. She has an Ed.D. in Learning Technologies and wrote this to share her thoughts and expertise with district leadership. The leaders were very open to the suggestions. Full disclosure: Santa Barbara Unified School District is entering a consulting relationship with Digital Promise and working with some of the CIRCL Educators in our Fall 2020 Professional Learning.

Summary

This article identifies the four major types of needs of a high school during distance learning. It suggests that we apply the Core Conceptual Framework and the TPACK framework when creating teacher professional development (PD); we choose a different type of learning management system; we curate research-based teaching practices intentionally and systemically; and we implement robust assessment and accountability measures.

Introduction

As a teacher, administrator, and scholar, my professional interests have always centered around developing strong pedagogical skills among our teachers. This document is intended to provide our district leaders with some suggestions to improve our instructional practices as we embark on distance learning. I wrote this from the perspective of a high school teacher and administrator based on my professional experience and expertise.

Background

In addition to writing a dissertation on game-based learning after participating in a hybrid program and engaged in different game-based learning projects, I have experience in a variety of asynchronous and synchronous learning and teaching activities. For example, my former students in Bakersfield, many of whom were English Language Learners or Bilingual students, participated in the asynchronous online writing mentoring project with 6th graders in Chicago. These experiences have afforded me a unique perspective on effective distance and hybrid learning.

Scope

There are numerous topics that are related to distance learning such as online security, student data privacy, and cyberbullying. Although I acknowledge that those topics are important, this document will primarily focus on online instructional practices in relation to teacher professional development (PD) and subsequent quality control of their teaching.

Needs

As the District implements 100% distance learning next school year, we must address the following needs:

- Needs of all learners including technological, linguistic, cultural, emotional, physical, and academic.

- Needs of parents who would want consistent, calibrated, highly-responsive, and personalized instructions for their students.

- Needs of teachers who provide distance learning to the students who they have never met and whose needs range from not having basic technology access to having an abundance of at-home resources in all areas.

- Needs of the community that is looking to the District to provide comprehensive yet flexible instructional solutions that will maximize all available financial and human resources.

Considerations

As we work to address the above needs, we must consider the following:

- Social-emotional needs of the staff, students, and parents.

- Successful distance learning requires strong relationships between the students and teachers, and we must address this issue prior to the beginning of any content-based instruction.

- Choosing and establishing a coherent instructional framework and/or theoretical framework to build our instruction practices.

- We must consider hardware, software, and how we leverage both hardware and software in a learning environment to achieve an optimal result. In order for our technology department to be effective, we must have resources, systems, and structures to address all three components that are grounded in a sound theoretical framework. This allows us to avoid chasing the latest and greatest technology tools unnecessarily. All leaders must act as a noise-canceler to be able to lead the teaching force by evaluating and advocating tools that meet our chosen instructional framework.

- Quality control over instructional practices.

- One of the biggest and most important tasks is to improve the overall quality of our instructions; we must consider this to be the moral imperative in whatever condition we educate our students.

- On-going monitoring of effectiveness beyond teacher- or student-preference

- We must develop a rigorous evaluation protocol that reveals the effectiveness of a tool or instructional practices.

Suggestions

To address the needs above, I suggest the following:

1. Teacher PD

- Address the needs of the teachers based on a Core Conceptual Framework immediately and urgently.

- According to Desimone (2009), effective teacher PD must (1) be content-focused (i.e. PD activities centered around the content that the teachers teach and how their students will learn it), (2) include active learning (i.e. participating in lesson studies, or group review and grading of sample student work), (3) be coherent (i.e. PD aligned with the teachers belief and knowledge; PD aligned with the goals of the district, site, and department based on a common instructional focus), (4) be over a period of time (i.e. PD spread different activities over a semester rather than a few days), and (5) facilitate collective participation (i.e. PD provided for a group of teachers who teach the same subject or in the same professional learning community).

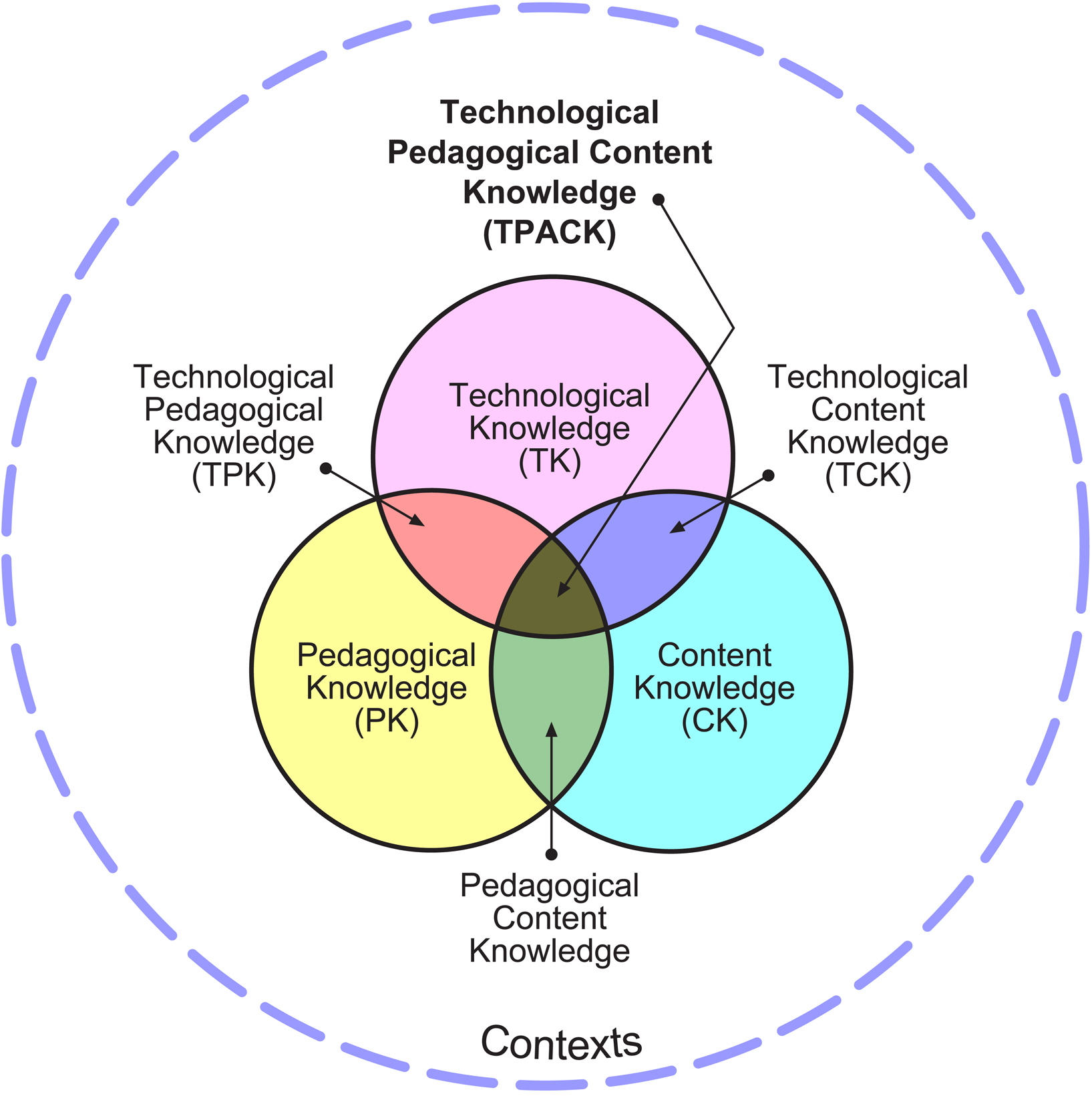

- Adopt the Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) Framework as the singular framework for teaching.

- Use the TPACK framework to guide the creation and evaluation of all PD offerings. TPACK framework addresses the needs for seamless integration of three major elements – technology, pedagogy, and content – in today’s educational environment (Koehler & Mishra, 2009). The TPACK model illustrates the importance of balancing all three such elements in forming a dynamic learning environment to improve student learning (Harris, Mishra, & Koehler, 2009; Mishra & Koehler, 2006).

The TPACK image. Adapted from “The TPACK Image,” by M. Koehler & P. Mishra, 2012.

- Provide personalized learning in all three areas of the TPACK Framework based on the Core Conceptual Framework.

- We should ensure that any online PD platform is able to provide the necessary training for our teacher to address all three areas of knowledge while addressing the needs of adult learners.

2. Technological tool

- Choose a singular learning platform that is robust and flexible.

- The District must choose a robust and flexible LMS that includes tools that strongly maximize student participation such as chats, wikis, forums, and blogs. It must allow an easy integration of tools such as all Google Apps and various video conferencing software. It must also provide detailed analytics and click counts that allow easy monitoring of the students’ activities. Finally, it must have tools to allow family engagement.

3. Teaching and learning practices

- Curate instructional practices that reflect best-practice that are based on research and data.

- Many resources that have been shared on our internal Google site Learning at Home for Teachers website are about digital tools. We must expand the site to include (1) the pacing guides, (2) major benchmarks, (3) assessment tools including performance rubrics, (4) the best practices, and (5) unit plans. For example, rather than just sharing the rubric for technology readiness for students, the site should include how a teacher would use it in his or her lesson. Rather than sharing the short videos on a topic, the site should provide examples of them being used in a lesson.

4. Assessment and accountability

- Continue collecting data around the effectiveness of each tool, pedagogical practices, and content acquisition.

- One of the benefits of distance learning is that we will have access to a great deal of data; therefore, we must build robust data analytics to quickly identify the area for growth so that we can respond with solutions.

- Provide a clear and concise plan for common practices among teachers.

- Distance learning, no matter how well planned, can be and is often a disorienting experience. Just as we ask our teachers to reduce the amount of content and set explicit expectations for their students, we must set 2-3 very clear expectations and adhere to those expectations.

Conclusion

This document is in no way a comprehensive document for distance learning. Because distance learning is not likely to go away any time soon, we must act now. We cannot afford to lose any valuable time before creating a comprehensive instructional plan, especially for our high school seniors who will experience significant loss. I look forward to working with our staff and district leaders to continue improving our practices.

Additional resources:

Assessment and Data toolbox from Dallas ISD

References:

Common Sense Media. (2020, April 07). Everything You Need to Teach Digital Citizenship. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.commonsense.org/education/digital-citizenship

Common Sense Media. (n.d.) Screen Time. Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/screen-time

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational researcher, 38(3), 181-199.

Educational Technology. (2012). The TPACK Model. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from http://www.rt3nc.org/edtech/the-tpack-model/

Harris, J., Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2009). Teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and learning activity types: Curriculum-based technology integration reframed. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(4), 393-416. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ844273.pdf

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1), 60-70. Retrieved from http://www.citejournal.org/vol9/iss1/general/article1.cfm

Magid, L., & Gallagher, K. (n.d.). The Educator’s Guide to Social Media. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.connectsafely.org/eduguide/

Michigan Virtual. (2020, March) Teaching Continuity Readiness Rubric. Retrieved June 18, 2020, from https://michiganvirtual.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Teacher-Continuity-Readiness-Rubric.pdf

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Quillen, I. (2013, March 7). Student Mentors: How 6th and 12th Graders Learn From Each Other. KQED Mind/Shift. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/27542/student-mentors-how-6th-and-12th-graders-learn-from-each-other#more-27542

Rappolt-Schlichtmann, G. (2020, March 18). Distance Learning: 6 UDL Best Practices for Online Learning. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.understood.org/en/school-learning/for-educators/universal-design-for-learning/video-distance-learning-udl-best-practices?_ul=1%2A1vi266z%2Adomain_userid%2AYW1wLUhYa3ZJQUFrcVNWb29EM0RzaExjUGc

Secondary Remote Learning Resources (n.d.) Learning at Home – Teachers. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://sites.google.com/sbunified.org/learning-at-home/secondary?authuser=2

StopBullying. (2020, May 07). What Is Cyberbullying? Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.stopbullying.gov/cyberbullying/what-is-it

Sung, K. (2015, October 27). Books-to-Games: Transforming Classic Novels Into Role Playing Adventures. KQED Mind/Shift. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/42538/books-to-games-transforming-classic-novels-into-role-playing-adventures

The PL Toolbox (n.d.) The PL Toolbox. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://www.thepltoolbox.com/