By Colin Hennessy Elliott & the SchoolWide Labs Team

This post was written by a member of the SchoolWide Labs research team, about their experience during the pandemic and what they learned from middle school science and STEM teachers as part of a larger Research-Practice Partnership between a university and a large school district in the United States. The post was reviewed by practicing Educator CIRCLS members. The purpose of the blog is to help open the door between the worlds of research and practice a bit wider so that we can see the differing perspectives and start a dialogue. We are always looking for more practitioners and researchers who want to join us in this work.

The COVID-19 pandemic pushed many school communities online last school year in the US. Teachers were charged with accommodating so many needs while holding levels of care and compassion for students and their families. As a multi-year research project aimed at supporting teachers in integrating computational thinking in science and STEM learning, we worked with renewed senses of compassion, creativity, and struggle. We witnessed how students and teachers innovatively developed computationally rich communication using the technologies from our project while teaching and learning remotely. Below we share a few moments from the 2020-21 school year that have helped us learn what it takes to engage middle school students in computational practices (i.e. collaborating on programming a physical system, interpreting data from a sensor) that are personally relevant and community-based. These moments offer lessons on how collaboration and communication are key to learning, regardless of whether the learning takes place in person or remotely.

Who we are

The SchoolWide Labs research team, housed at the University of Colorado Boulder with collaborators at Utah State University, has partnered with Denver Public Schools (DPS) for over five years. We work with middle school science and STEM teachers to co-develop models for teacher learning that support the integration of computational thinking into science and STEM classrooms. The team selected, assembled, and refined a programmable sensor technology with input from teachers on what would be feasible in their classrooms and in collaboration with a local electronics retailer (SparkFun Electronics). This collaboration focused particularly on programmable sensors because they offer opportunities for students to develop deeper relationships with scientific data, as producers rather than just data collectors.1 This aligns with modern scientific practice where scientists often tinker with computational tools to produce the data they need to answer specific questions.

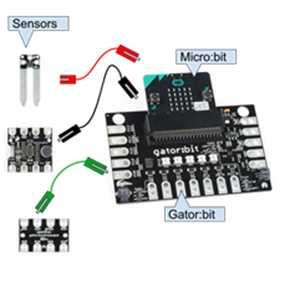

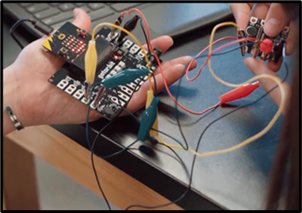

The Data Sensor Hub (DaSH) is a low cost physical computing system used in the curriculum and professional learning workshops developed by the SchoolWide Labs team. Ensuring the DaSH would be low cost was a priority of the team as an issue of access and equity. The DaSH consists of the BBC Micro:bit, a connection expander called the gator:bit, and an array of sensors that can be attached to the micro:bit and gator:bit with alligator clips (see Figure 1). Students can easily assemble the DaSH themselves to experience the physical connections and hard wiring. Students and teachers can write programs for the DaSH using MakeCode, a block-based programming environment that can be accessed via a web browser, making it easy to use with various computer setups. For students with more programming experience, MakeCode has the option to use python or javascript to program the micro:bits.

Figure 1.The Data Sensor Hub (DaSH). The picture on the left depicts the components of the DaSH used with the Sensor Immersion Unit including the micro:bit, Gator:bit and three sensors (top to bottom: soil moisture sensor, microphone sensor, environmental sensor). The picture on the right shows a teacher and student interacting with the DaSH set up just for the microphone sensor.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, our research team co-designed curricular units with teachers interested in using the DaSH to engage middle school students in scientific inquiry. Currently there are four units available on our website, three that use the DaSH and one that uses a 3-D printer. The Sensor Immersion Unit – the only unit teachers implemented remotely in the 2020-21 school year – has students explore the DaSH in use via a classroom data display, learn basic programming, and create their own displays that collect environmental data (sound, temperature, carbon dioxide levels, or soil moisture) to address a question of their choice. For example, one group of students decided to investigate climate change by measuring atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in their neighborhoods and exploring the impact of plants and trees. The goal is for students to develop ownership of the DaSH as a data collection tool by wiring the hardware and programming the software. In the process, they engage in computational thinking and computationally rich communication when they discuss their use of the DaSH with peers and the teacher.

In the 2020-21 school year most middle schools in Denver Public Schools were remote. Several STEM teachers, with more curricular flexibility, decided to provide DaSHs to students who wanted the responsibility of having them for a period of time. Having the DaSHs in students’ homes offered opportunities to make the barriers between home and school less visible, as students conducted place-based investigations and emergently took on the role of data producers. For example, some students shared temperature data and carbon dioxide levels in and around their homes with the class. In these moments, students emergently took on the role of data producers. Below, we share two examples from observing student and teacher interactions in virtual mediums which helped our research team learn about what is possible using the DaSH. We also developed new supports to help teachers facilitate extended student collaboration and communication when using the DaSH.

Lesson Learned 1: Increasing student collaboration in virtual settings

One middle school STEM teacher, Lauren (a pseudonym), had the opportunity to teach different cohorts of eighth graders in the first two quarters of the 2020-21 school year. A new SchoolWide Labs participant, she was enthusiastic about implementing the Sensor Immersion Unit with her first cohort in the first quarter. She navigated the logistical challenges of getting DaSHs to over half her students along with the pedagogical challenges of adapting the curriculum to a remote setting. After her first implementation, she shared that she was disappointed that her students rarely collaborated or shared their thinking with each other when they were online. We heard from other teachers that they had similar struggles. Before Lauren’s second implementation, we facilitated several professional learning sessions with the aim of supporting teachers to elicit more student collaboration in remote settings. Through our work together, we identified the importance of establishing collaboration norms for students, offering continued opportunities to meet in small groups virtually, and modeling how to make their work visible to each other. In Lauren’s second implementation with new students during next quarter, she intentionally discussed norms and roles for group work in “breakout rooms,” or separate video calls for each group (her school was not using a software that had the breakout room functionality). One of the resulting virtual rooms with three eighth graders during the Sensor Immersion Unit was especially encouraging for both Lauren and our research team. Without their cameras on at any point, the three boys shared their screens (swapping depending on who needed help or wanted to show the others) and coordinated their developing programs (on different screens) in relation to the DaSHs that two students had at home. Their collaboration included checking in to make sure everyone was ready to move on (“Everyone ok?”) and the opportunity to ask for further explanation from others at any point (“hold on, why does my [DaSH]…”). With their visual joint attention on the shared screen, the three successfully navigated an early program challenge using their understanding of the programming environment (MakeCode) and hints embedded in it (developed by the research team).

Lesson Learned 2: Adapting debugging practices to a virtual environment

Many science and STEM teachers new to our projects have struggled with finding confidence in supporting students as they learn to program the DaSH. They specifically worry about knowing how to support students as they debug the systems, which includes finding and resolving potential and existing issues in computer code, hardware (including wiring), or their communication. This worry was further magnified when learning had to happen remotely, even with some students having the physical DaSH systems at home. Common issues teachers encountered in student’s setup were consistent with the bugs that we have identified over the course of the project including: 1) code and wiring do not correspond, 2) problems in the students’ code, 3) the program is not properly downloaded onto the micro:bit, and more.2

Being unable to easily see students’ physical equipment and provide hands-on support made some teachers wary of even attempting to use the SchoolWide Labs curriculum in a remote environment. However, those teachers who were willing to do so made intriguing adaptations to how they supported students in identifying and addressing bugs. These adaptations included: 1) meeting one on one briefly to ask students questions about their progress and asking them to hold up their systems to the camera for a hardware check, 2) holding debugging-specific office hour times during and outside of class time, and 3) having students send their code to teachers to review as formative assessments and debugging checks. Although debugging required more time, patience, and creativity from teachers and students, these activities were generally successful in making the DaSHs work and helping students become more adept users.

Future Directions

As teachers and students have gone back to attending school face-to-face, the lessons learned during remote instruction continue to inform our work and inspire us as a SchoolWide Labs community. As these two examples show, the ingenuity of teachers and students during a tough shift to virtual learning led to new forms of computational thinking, communication, and collaboration. It became more clear that there was a critical need for at least some students to have the physical systems at home to deeply engage in the process of being data producers, which is indicative of the curriculum being so material rich. Yet, simply having the the DaSH in hand did not ensure that students would participate in the kinds of communication important for their engagement in and learning of the targeted science and computational thinking practices. While we continue to explore the complexity of teacher and student interactions with the DaSH, this past summer and fall we have been working with participating teachers (new and returning from last year) to develop a more specific set of norms, which include small group communication norms and roles. Additionally, we have begun to consider other strategies that may support students to learn programming and debugging skills, such as the use of student-created flowcharts to represent their view of the computational decisions of the DaSH. The shift to virtual learning, and now back to face-to-face instruction, has required us to more deeply reflect on the professional learning that best supports teachers in using the DaSH and accompanying curriculum in a variety of instructional settings, with both anticipated and unanticipated constraints. We welcome the opportunity to continue learning with and from our colleagues who are similarly engaged in this type of highly challenging but extremely rewarding endeavor to promote computationally rich and discourse-centered classrooms.

More Information

More on SchoolWide Labs work:

- Visit our website.

- Gendreau Chakarov, A., Biddy, Q., Hennessy Elliott, C., & Recker, M. (2021). The Data Sensor Hub (DaSH): A Physical Computing System to Support Middle School Inquiry Science Instruction. Sensors, 21(18), 6243. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21186243

- Biddy, Q., Chakarov, A. G., Bush, J., Hennessy Elliott, C., Jacobs, J., Recker, M., Sumner, T., & Penuel, W. (2021). A Professional Development Model to Integrate Computational Thinking Into Middle School Science Through Codesigned Storylines. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 21(1), 53–96.

- Gendreau Chakarov, A., Recker, M., Jacobs, J., Van Horne, K., & Sumner, T. (2019). Designing a Middle School Science Curriculum that Integrates Computational Thinking and Sensor Technology. Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287476

Important references for our work

Hardy, L., Dixon, C., & Hsi, S. (2020). From Data Collectors to Data Producers: Shifting Students’ Relationship to Data. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(1), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2019.1678164

Weintrop, D., Beheshti, E., Horn, M., Orton, K., Jona, K., Trouille, L., & Wilensky, U. (2016). Defining Computational Thinking for Mathematics and Science Classrooms. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-015-9581-5

______________________

1 See Hardy, Dixon, and Hsi(2020) for more information about data producers and collectors.

2 Table 2 in Gendreau Chakarov et al. (2021) has a full list of common DaSH bugs students have encountered across the project.

Author: Aditi Mallavarapu

Author: Aditi Mallavarapu

Who is Marni Landry?

Who is Marni Landry?