By Angie Kalthoff

Neuroscience tells us the brain feels safest and most relaxed when we are connected to others we trust to treat us well.

I recently participated in an informal conversation with other educators where we were discussing teaching and learning in a distance learning setting. Current teachers were sharing ice breakers and back to school activities that they were finding for their very different-than-normal back to school. I asked for resources around how to talk to kids about their current situations due to the state of the world. People are dealing with a lot of emotions right now. World events like a pandemic, wildfires, and social justice conversations around the murder of George Floyd are a lot for adults to digest. I can’t even imagine how children or teens are processing it all. In this conversation, no one had a resource to share that was specific to online learning but we did talk about Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain by Zaretta Hammond. I learned about this book when I was a technology integrationist. Additionally CIRCL Educators has been focusing on it, and other books and topics related to social justice, bias in algorithms, techequity, and other anti-racist practices over the past few months.

In Ms. Hammond’s book, I learned about the importance of trust. Research shows that a positive relationship between students and teachers is crucial for students to reach their fullest potential. Of course! Ask any educator and they can talk to you about the importance of relationships and trust. I experienced this early on in my teaching career. But, if you would have asked me to explain why, I wouldn’t have been able to connect it to the research and history shared in this book. This phenomenon is rooted in our history, from the time when humans roamed the earth and started to live in communities to get protection from animals. From these experiences, it is thought that the brain created a social engagement system to ensure humans form communities, build trustful relationships, and work to maintain them. In this post I will present an introduction to help you understand how to use the research around neuroscience in your classroom to influence positive behaviors, discuss why we developed these systems, and how this relates to your classroom with a culturally responsive response in mind.

To start, if you are new to Culturally Responsive Teaching (CRT), one of the questions I continually ask myself is “am I thinking of my students whose lived experiences are different than mine and what perspectives am I not thinking about?” in her books she focuses on “How do I treat my students who are different from me? They could have a different skin color, they could speak a different language, they could have different abilities than I do, and have different lived experiences. And, am I building their self esteem or am I creating the positive affirmations that will benefit them in life outside of my classroom?” Ms. Hammond defines CTR as the process of using familiar cultural information and process to scaffold learning. She emphasizes communal orientation and focuses on relationships, cognitive scaffolding, and critical social awareness.

I began my teaching career as an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher in 2008. This title has now transitioned to Multi-Lingual and has also been referred to as English Language (EL) teacher and teacher to English Language Learners (ELL). Many of my students spoke more than one language and I appreciate the thought that has gone into the transition of the title. I learned a lot about teaching and the importance of relations early in my career. As a white teacher, who grew up in the MidWest, my background and lived experiences are very different than many of my students. While students in my classroom moved to Minnesota from all over the world, a large part of my student population came from refugee camps in Somalia. It was during this time I learned about the importance of building trust with students and families. I wish I had a resource like Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain but I didn’t. In this post, I will share specific research based practices that you can take into your classroom whether it is online in a virtual settings or in person in a physical building.

Neuroscience for Teaching Practice

Affirmation

When your brain feels safe and relaxed it sends oxytocin (the bonding hormone) out which in turn makes us want to build trusting relationships with the people we are engaging with. Neuroscience tells us the brain feels safest and most relaxed when we are connected to others we trust to treat us well. How does the brain know when to do this? In most people, the brain releases oxytocin when any of these actions happen:

- Simple gestures

- A smile

- Nod of the head

- Pat on the back

- Touch of your arm

Affirmation in your school environment.

One way that you can bring this into your learning situation is through an affirmation. In the book, a study is described where a principal takes the time to greet each student by giving them her full attention, getting to their level, and offering a bow. Students in this study would light up based on this affirmation and respect, both figuratively and literally.

Mirror Neurons

When we are around others in that we have a trusting relationship with, mirror neurons may help keep us in sync with them. Some researchers think mirror neurons help us have empathy with others. Additionally, they may help us make and strengthen bonds. Have you ever thought about why you smile when someone smiles at you? This action may be connected to the mirror neuron system. Early studies showed that mirror neurons mirrored what you see. For example, when we see a behavior such as smiling, mirror neurons in the region of our brain that relate to smiling activate. Some researchers believe that we also mirror the behavior we see by also performing the behavior (smiling in this example) and that this mirroring signals trust and rapport.

This section had me searching the Internet for more information and one analogy that often came up was “Monkey See, Monkey Do.” This makes me think about young children and babies. Have you ever had an interaction with a young one where they try to copy a noise, facial expression, or gesture, it may be related to the mirror system. You can watch this introductory video if you want to learn more. (It’s from early on when we were just starting to learn about mirror neurons, but it presents many questions that researchers are still investigating.) Note, the mirror system is fascinating but there is still much research to be done to fully understand it.

Mirror Neurons in your school environment.

While researchers are still learning more about how the mirror system works, many of the big ideas discussed are important for practice. We definitely have areas in our brains that help make us feel connected to others. It may well be that the synchronized dance of mirror neuron systems between people is what is responsible, or it may be something else. Regardless, there is no doubt that connections are related to feeling more relaxed and trusting — important for learning. As a teacher, it really is important to make a personal and authentic connection with your students.

To apply the research from this chapter and begin building a different kind of relationship there are two things you can start working on today that relate to empathy and connection; listening with grace and building trust.

To Listen with Grace

In chapter five there are a few examples of how to listen with grace. They include:

- Give one’s full attention to the speaker and what is being said

- Understand the feeling behind the words and be sensitive to the emotions being expressed

- Suspend judgement and listen with compassion

- Honor the speaker’s cultural way of communicating

I know we are all so busy that it’s hard to sometimes take the time to be fully present, but listening and connecting in whatever ways we can is even more important in the online space.

Trust Generators

In the book, Zaretta Hammond shares five ways to help create trust, I will discuss one of those, Selective Vulnerability. I chose Selective Vulnerability due to the state of the world we are living in as we live through a pandemic. Our lives and routines have changed. For many, this means taking what we have known as education and changing it drastically. Educators who have been teaching in classrooms for their whole careers are now expected to move to an online environment. Children who have benefited from the in person learning environment are now having to learn from a device outside of school. I think, as a learning community, we might all benefit from selective vulnerability. CIRCL Educator Sarah Hampton and I both agree that there is room to grow in being transparent with students in our own growing pains as learners.

Trust Generator: Selective Vulnerability

Definition: People respect and connect with others who share their own vulnerable moments. It means showing your human side is not perfect.

What It Looks Like: Sharing with a student a challenge you had as a young person or as a learner. Sharing new skills you are learning and what is hard about it. In either case, the information shared is carefully selected to be relevant. Think about who you are talking to and what you have in common. The goal here is to connect and show that you are a fallible human being. A student with a very different background may not be able to understand certain examples and there is the possibility that your example could alienate rather than build rapport.

As I mentioned before, one of the important questions in the book is “How do I treat my students who are different from me?” I think the focus of thinking about the perspective of the person in the interaction is so important. This year has brought so much for all of us to deal with, and as teachers, we need to know who we are talking to and what experiences have shaped them, so that we can work to make connections as a foundation for teaching and learning. If you want to dig deeper into listening with grace and building trust, Ms. Hammond has that and so much more in her book.

What do you think? Connect with us on social media @CIRCLeducators and share how you show affirmation to your students!

Aaron Hawn

Aaron Hawn Nancy Foote

Nancy Foote

by Sarah Hampton

by Sarah Hampton

by Merijke Coenraad

by Merijke Coenraad by Sarah Hampton

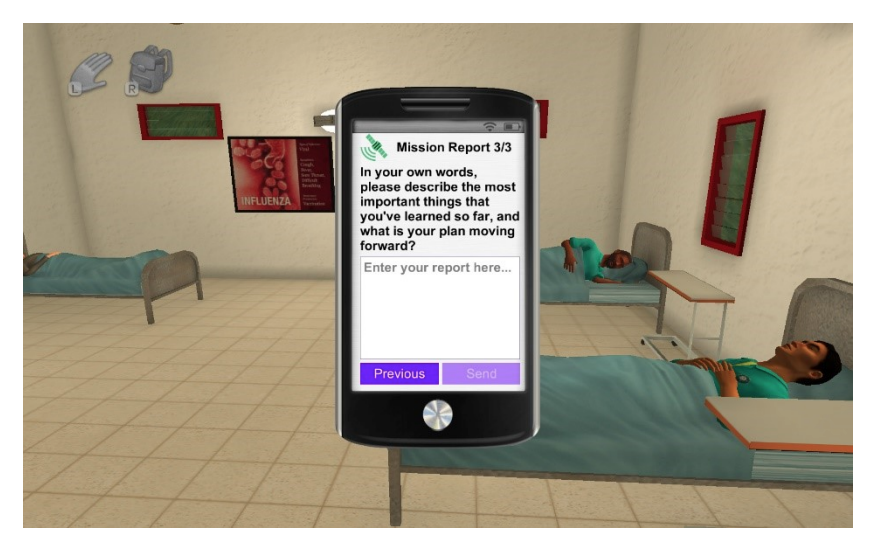

by Sarah Hampton In-game reflection prompt presented to students in Crystal Island

In-game reflection prompt presented to students in Crystal Island