by Kip Glazer Ed.D.

Summary

In a distance learning environment, assessment can become much more challenging. This article makes six suggestions as to how a high school teacher can assess students effectively to improve student learning.

Introduction:

In my first article, I made four suggestions to support our staff in a distance learning environment. This article will focus on the importance of assessment and how we should leverage that in the new era of learning, sometimes only remote and sometimes without large-scale standardized assessments. I suggest teachers consider six different ways to leverage assessment to improve student learning:

- Ask your students to create tests and quizzes

- Integrate student-created tests and rubrics

- Focus on critical assessing skills

- Give students a place to interact meaningfully

- Leverage peer evaluation to scaffold student learning

- Create consistency in grading across all similar courses

Background

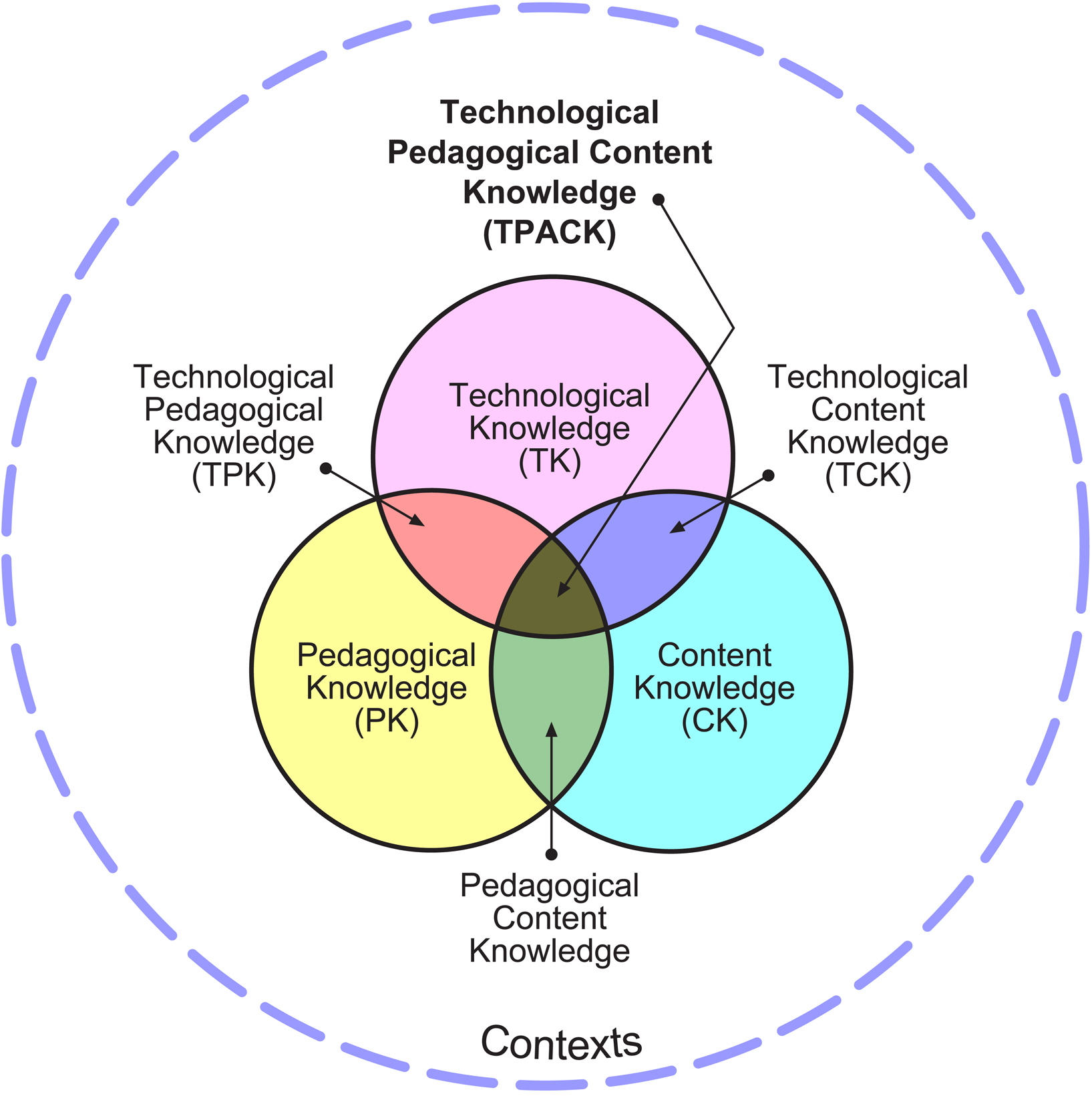

Many teachers are trained to create learning experiences for our students known as teaching. Especially for secondary teachers, teaching includes creating lesson plans that deliver specialized content to our students and then giving the students assessments (i.e. quizzes and tests) to gauge what the students have learned. However, in an online learning environment, traditional assessments such as quizzes and tests are not as effective due to altered learning environments.

In an in-person learning environment, many teachers rely on the publisher’s test bank or textbook questions for assessment for a variety of reasons including a teacher’s desire to align his or her assessment to the approved curriculum that a teacher is asked to deliver. Others use them to save time; some use them because they don’t feel confident enough to create their own assessments. Over the years, I have worked with many teachers who were not terribly thrilled with the quality of the publisher’s assessments yet used them because they felt that they were not skilled to create test questions. Even if a teacher is well-trained in generating effective assessments, they often struggle to create them as constructing valid assessments takes time and expertise. Furthermore, high school teachers have the added pressure of preparing students for high stakes standardized tests such as the SAT, ACT, or AP that are created by experts. Even if a teacher knows and wants to implement skill- or competency-based assessment, the pressure to prepare his or her students for standardized tests can create tension. I personally experienced this as an AP English Literature teacher for many years.

Scope

Having only had high school teaching experiences, I do not presume to know a lot about how this article will apply to the K-6 setting. Although some of the suggestions will likely be applicable to the 7-12 setting, I do not presume to be an expert in every subject being taught in secondary schools. I intend to provide a few examples and strategies that are grounded on sound learning theories so that the teachers can augment their instructional practices should they find this article useful.

Needs

High school teachers need their instructional leaders to provide a clear and concise standard for instruction and assessment as the results of assessment lead to grades that are reviewed by the colleges as a factor in the college-admission decisions. Variability in assessments, therefore, is directly related to many practical and long-lasting consequences. Furthermore, having a clear understanding of what is being assessed and how it will be assessed can guide instructional practices. Having good assessments is vital in measuring the effectiveness of teaching and learning.

Suggestions

In order to maximize the impact of the assessment, I suggest 6 assessment practices. The suggestions are rooted in Papert’s Constructionism.

Learning, according to Papert, is both situated and pragmatic, and the construction of artifacts to demonstrate learning are not only useful but imperative (Papert & Harel, 1991). I argue that we focus on moving towards more student-created assessments.

1. Ask your students to create tests and quizzes

I suggest that the teachers use fact-based and time-bound quizzes and tests as learning tools rather than as grade-bearing assessments by allowing your students to create them.

In an online environment, students tend to have more resources available on their fingertips including their peers. It is not uncommon for your students to have additional off-line conversations while they are in your class, known as the “dual-screen interactivity” (Nee & Dozier, 2017, p.5). Examples of dual-screen interactivity include searching for additional information in addition to looking at the primary screen, connecting with others who are interacting with the same content, and creating external posts such as social media posts or memes. (Nee & Dozer, 2017). In fact, a teacher should expect this behavior to happen. Rather than fighting against them, I suggest you leverage them for learning.

For example, consider giving a group of students a section of a textbook to create multiple-choice, true-false, or sequential questions. I used this strategy often when I taught social studies where the knowledge of facts is very important. Not only did each group have to create the quiz questions, but each group also had to explain why they chose the topics and the content to be included in the test. Once the students created the questions, I had others in the class take the quiz to verify that the questions were of high quality based on the justifications provided by the authors of the questions. Then I as the teacher chose questions that I thought were great and added them to the official assessments. This practice allowed my students to interact with the materials multiple times without having to listen to a lecture. Also, this taught the students to look for critical information rather than focusing on obscure facts to trick each other. Finally, this allowed me, the teacher, to leverage the four out of five principles of game-based learning, such as competition and goals, rules, choices, challenges, (Charsky, 2010) as students to compete for the coveted position of becoming the author of the final assessment. Even if a group chose to find the questions online, they had to figure out the justifications and answers, which was harder to copy.

2. Integrate student-created tests and rubric

If you are teaching a course such as English, where foundational skills development becomes the center of the course rather than acquiring more discrete information, I suggest you encourage your students to create the rubric that they can use to grade their own learning as student-created tests and rubrics can improve student agency in learning. I used to have my students research various rubrics and evaluate them and create their own to evaluate each other’s work.

According to Garrison and Ehringhaus (2007), students learn best when they are involved in the assessment process. By allowing the students to be a part of their rubric creation, a teacher can not only improve student learning but also assess what they know about the skills that they are being taught.

3. Focus on assessing critical skills

When I say skills, I mean quoting, citing, summarizing, paraphrasing, and video creation. Because students have unrestricted access to additional resources, being able to create new content to demonstrate what they learned is becoming increasingly important. No matter how much teachers try to secure their assessments, a student can always take a screenshot and share it with other students. If the test only requires recalling facts, it is likely to be ineffective in measuring the authentic level of learning. Rather than spending time to limit access to additional resources, I suggest teachers encourage students to add in new information and then the teachers should examine the new information to understand why the students thought it was important to include in their final products.

Mathematics teachers can also encourage students to find the problems online that assess the procedures and content of the lesson and ask the students to explain why a question should or should not be included in a future assessment. They can also take it a step further and ask the students to create an instructional video and have them evaluate each other’s video to see which one provided the clearest instruction.

4. Give students a place to interact meaningfully around the subject matter

I also suggest using a discussion forum as an assessment tool. According to Balaji and Chakrabati (2010), a robust online discussion forum has a significant positive effect on student participation and learning. However, the forum should not be used as one more place where the teacher can ask questions of their students. An online forum should be a place where students pose questions of others. Also, teachers should not consider the number of posts as the indicator of student engagement and learning (Song & McNary, 2011). Instead, teachers should encourage the students to pose better questions to each other based on Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (1997, 1999 & 2005).

5. Leverage peer evaluation to scaffold student learning

As teachers leverage peer-to-peer interactions to improve earning, I suggest that teachers leverage peer feedback as a component of every assessment.

For example, I used an embedded feature of the star rating system when I used the discussion forums. Rather than posing questions for my students to answer, I asked my students to create 2-3 questions each week based on their reading. Then they would be required to answer 2-3 questions that were posed by other students in the class. If they discovered that the questions were similar or identical to what they posted, they were to post one additional question to indicate that someone else already posted the same question, which encouraged them to get to the forum quicker than the others. As they answered each other’s questions, they were also encouraged to critique the quality of the question by giving them 1-5 stars. Once again, they were to provide feedback as to why they gave the stars based on Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (1997, 1999 & 2005). After a few rounds of questioning, I asked the students to justify why they felt that DOK level 1 and 2 questions were necessary for some context.

6. Create consistency in grading across all similar courses

Finally, I suggest leveraging the Professional Learning Community (PLC) to create consistency in grading across all similar courses. Even more so in a distance learning environment, parents and students may feel that their students are not being fairly assessed based on their personal feelings and perceptions rather than what is actually happening in the class. I strongly suggest that each PLC creates common practices around the type and frequency of assessments for the benefits of all PLC members to reduce subjectivity among all its members in regards to how their students are being assessed. In a distance learning environment, sharing expertise and saving time around assessment is not only useful but also vital to all of us as it will allow us to preserve our most precious commodity: our time.

Specific considerations for Educators

As we discuss assessment, we should consider the following:

- Even though a grade can be an indication of student learning, we must look at assessment independent of grades as there are many ways to assess student learning without assigning a grade.

- Unfortunately, many high school students will not take an assessment seriously unless there is a grade attached. Therefore, any discussion around assessment in high school should address the connection between assessments and grades.

- In an online environment, traditional assessments that are time-bound and facts-based are not as effective as many opportunities to circumvent even the most effective security measures.

- Additionally for California Educators – The California Education Code 49066 (a) states, “When grades are given for any course of instruction taught in a school district, the grade given to each pupil shall be the grade determined by the teacher of the course and the determination of the pupil’s grade by the teacher, in the absence of clerical or mechanical mistake, fraud, bad faith, or incompetency, shall be final.” In other words, teachers have the final say in a grade.

Conclusion

Being able to accurately assess student learning is one of the most challenging parts of being an effective teacher. We (teachers and administrators) often used our state-based large-scale standardized assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of our teaching. As states suspend these conventional tests that may not have been the most effective way to assess our teaching, we need to look to new assessment options. The absence of these tests may be a great opportunity for us to look at assessment from a completely different perspective. As we move forward with the 100% distance learning model, I urge instructional leaders to pay close attention to how teachers are assessing their students. By paying close attention to our assessment practices, we will be able to improve our understanding of student learning considerably.

Additional resources:

Authentic Assessment – Indiana University, Bloomington

Introduction to competency-based Education – Aurora Institute

References:

Ackermann, E. (2001). Piaget’s constructivism, Papert’s constructionism: What’s the difference? Retrieved from http://learning.media.mit.edu/content/publications/EA.Piaget%20_%20Papert.pdf

Aurora Institute (n.d.). Introduction to Competency-Based Education. Retrieved July 26, 2020, from https://aurora-institute.org/our-work/competencyworks/competency-based-education /

Balaji, M.S., & Chakrabati, D. (2010). Student interactions in online discussion forum: Empirical research from “Media Richness Theory” perspective. Journal of Interactive Online-Learning, 9(1), 1-22.

California Legislative Information (n.d.). California Law. Retrieved July 26, 2020, from http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=EDC§ionNum=49066.

Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning (n.d.). Assessing Student Learning: Authentic Assessment. Retrieved July 26, 2020, from https://citl.indiana.edu/teaching-resources/assessing-student-learning/authentic-assessment/index.html

Charsky, D. (2010). From edutainment to serious games: A change in the use of game Characteristics. Games and Culture, 5(2), 177-198. doi:10.1177/1555412009354727

Garrison, C., & Ehringhaus, M. (2007). Formative and summative assessments in the classroom.

Nee, R. C., & Dozier, D. M. (2017). Second screen effects: Linking multiscreen media use to television engagement and incidental learning. Convergence, 23(2), 214-226.

Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. In Constructionism. Retrieved from http://www.papert.org/articles/SituatingConstructionism.html

Song, L., & McNary, S. W. (2011). Understanding Students’ Online Interaction: Analysis of Discussion Board Postings. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 10(1).

Webb, N. L. (1997). Criteria for Alignment of Expectations and Assessments in Mathematics and Science Education. Research Monograph No. 6.

Webb, N. L. (1999). Alignment of Science and Mathematics Standards and Assessments in Four States. Research Monograph No. 18.

Webb, N. L. (2005). Web alignment tool. Wisconsin Center of Educational Research. University of Wisconsin-Madison.