by Pati Ruiz

Critical pedagogy seeks to transform consciousness, to provide students with ways of knowing that enable them to know themselves better and live in the world more fully.

—bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress

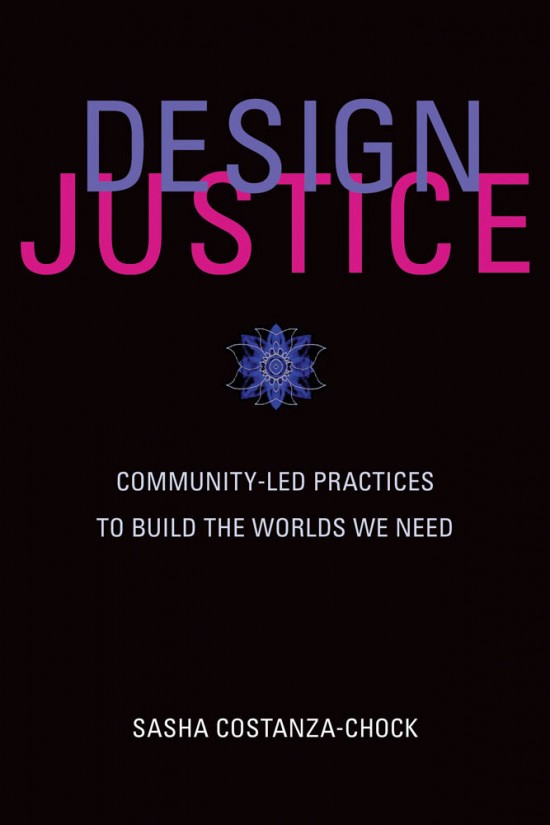

Written by Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, explores the relationships among design, power, and social justice. I was drawn to this book because it centers those who are intersectionally disadvantaged, this refers to individuals that might have multiple minoritized identities and originally refered to the oppression of African American women. It also shares the work done by Design Justice Network (DJN) to “build a better world, a world where many worlds fit.” The Design Justice Network is “an international community of people and organizations who are committed to rethinking design processes so that they center people who are too often marginalized by design.” This network is a community of practice that is guided by a set of 10 principles; I am a DJN signatory. I hope this short post prompts you to read the whole book that was made available for free on PubPub (the open-source, privacy-respecting, all-in-one collaborative publishing platform) or sign up for the Design Justice Network newsletter to learn more. This book has really inspired me to think differently about design and what it takes to truly make design accessible.

What is Design Justice?

The book begins with a definition, or “tentative description” of design justice:

Design justice is a framework for analysis of how the design of technologies, tools, and learning environments (to name a few) distributes benefits and burdens between various groups of people. Design justice focuses explicitly on the ways that design reproduces and/or challenges the matrix of domination (white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, capitalism, ableism, settler colonialism, and other forms of structural inequality). Design justice is also a growing community of practice that aims to ensure a more equitable distribution of design’s benefits and burdens; meaningful participation in design decisions; and recognition of community-based, Indigenous, and diaspora design traditions, knowledge, and practices (p. 23).

After a comprehensive overview of the values, practices, narratives, and site/locations of design, the book turns to the pedagogies of design in Chapter 5. In this chapter, the author focuses on answering the question: How do we teach and learn about design justice?

Costanza-Chock responds to this question by writing “I don’t believe there is only one way to answer this question, which is why I use “pedagogies” in the plural form.” Among the pedagogies described in the chapter are:

- Paulo Freire’s educación popular or popular education (pop ed)

- critical community technology pedagogy

- participatory action design

- data feminism

- constructionism, and

- digital media literacy

Exploring Design Justice Pedagogies

In our previous work, as CIRCL Educators, we wrote about constructionism. This pedagogy is one that teachers often turn to and as Costanza-Chock notes, it is not one that is “explicit about race, class, gender, or disability politics.” However, it should center the social and cultural aspects of learning, the construction of knowledge in the learner, and the learner’s contexts (e.g.a student’s racial/ethnic background, social class, and other social identities). Furthermore, Costanza-Chock writes that “in a constructionist pedagogy of design justice, learners should make knowledge about design justice for themselves and do so through working on meaningful projects. Ideally, these should be developed together with, rather than for, communities that are too often excluded from design processes.”

Hand in hand with the pedagogies described in this chapter is the decolonization of design practices, which refers to deconstructing Western privilege of thoughts and approaches. Those involved in the decolonizing design movement advocate for a global approach to design that rethink historical narratives and seek to center design practices erased or ignored in Eurocentric design practices. As Costanza-Chock describes “design justice pedagogies must support students to actively develop their own critical analysis of design, power, and liberation, in ways that connect with their own lived experience.” As teachers and educators, our role is to figure out a way to overcome existing design challenges so that our students can implement just design principles.

Principles of Design Justice

What are practical examples of what teaching about design justice looks like? Based on the author’s experiences in her own courses, 10 principlesillustrate what this movement envisions:

Principle 1: We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

Principle 2: We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

Principle 3: We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

Principle 4: We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

Principle 5: We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

Principle 6: We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

Principle 7: We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

Principle 8: We work towards sustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

Principle 9: We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

Principle 10: Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

At Educator CIRCLS we are at the beginning of our conversation around AI in Education. These design justice principles will be front of mind as we continue to consider and discuss the variety of ways AI technologies are currently being developed and employed. Please let us know your thoughts by tweeting @EducatorCIRCLS and sign up for the CIRCLS newsletter to stay updated on emerging technologies for teaching and learning.