By Judi Fusco

This post features the dissertation work of Michaela Jacobsen, Ed.D (completed March, 2019). She is currently Assistant Principal at Louis E. Stocklmeir Elementary School in the Cupertino Union School District.

In her dissertation, she investigated:

1) What supports teachers need when they are actively leading and designing their own professional learning.

2) How teacher beliefs about learning relate to how they participate in an active professional learning program.

3) How teachers beliefs about teaching and learning change from beginning to end of the experience.

We are currently in a time of uncertainty about so many issues. During this past spring, teachers experienced a time when everything changed. The work by Dr. Jacobsen looks into the importance of thinking about beliefs during a change process. While her work looked at a set of specific conditions around change, she found important considerations for any situation where people are asked to change.

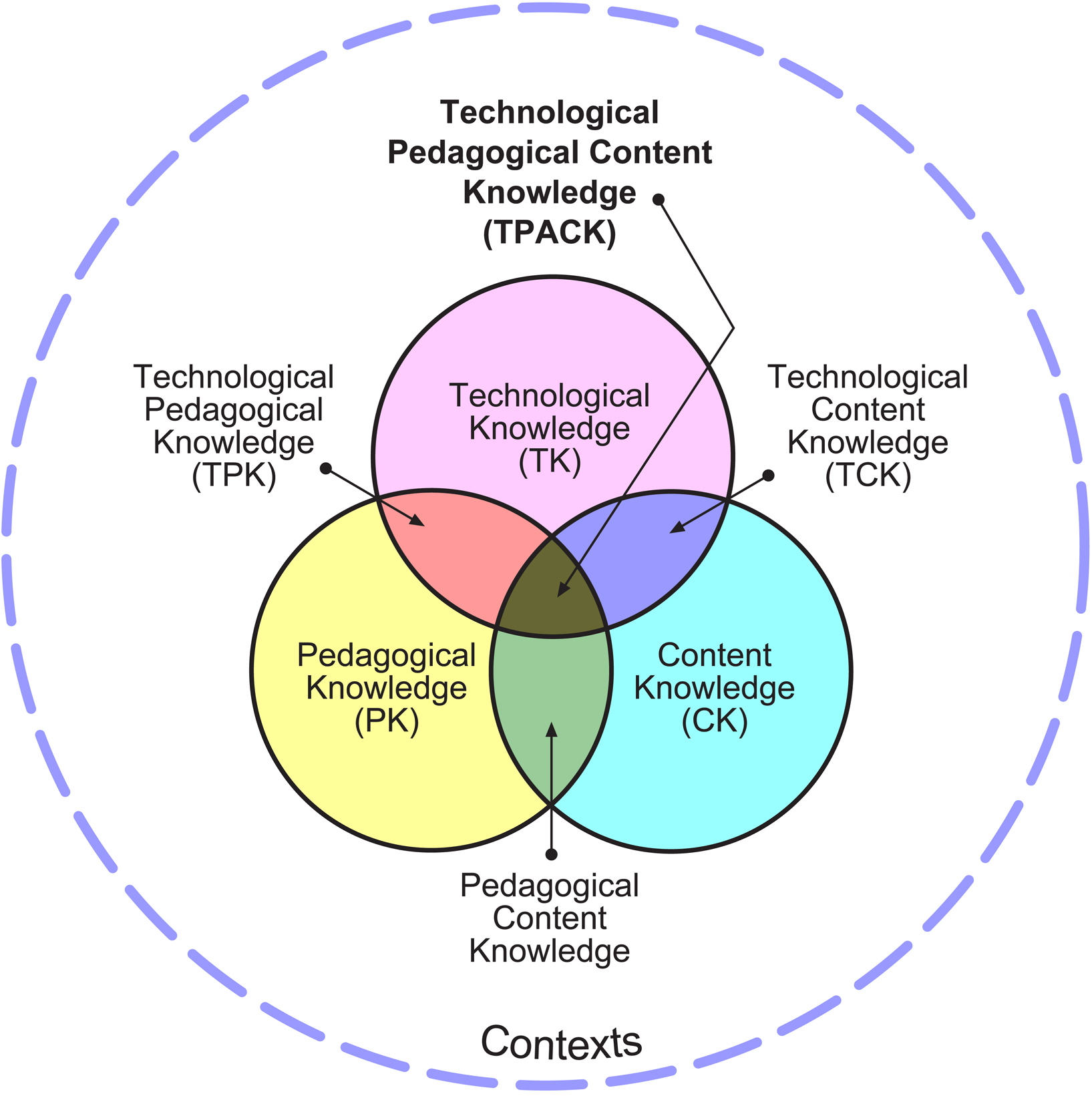

We know from past research that effective professional learning promotes active learning, emphasizes collaboration, is sustained over time, is related to teachers’ specific contexts and curriculum, and is coherent with the school as a whole. Over the school year, Dr. Jacobsen worked with the three teachers. The school principal and vice principal also offered support. The three teachers and Dr. Jacobsen, who acted as a facilitator for the group, devoted much of their school-based professional learning time to work together. A problem-based learning (PBL) approach was the method.

In PBL, learners work to solve authentic, ill-structured problems with a facilitator. The facilitator helps establish a culture of collaboration in developing a deep shared understanding of the problem and possible solutions. Facilitators also model good problem solving strategies and refrain from giving answers. In PBL, learners gain knowledge as they work together and discuss and reflect around the problem to be solved. PBL was chosen because it promotes active inquiry, the acquisition and deepening of problem-solving skills, self-direction, reflective practices, and collaboration and communication skills. These are important for all learners, but especially important for professionals.

Together, the three teachers chose a problem around how to adopt a new practice, specifically how to help students become better problem solvers in math. All the teachers felt that learning how to help students become better problem solvers would be challenging, but agreed it would be an important problem to solve. Math was taught in a very traditional instructional manner in their school and the new practice of putting the learner at the center did not fit particularly well in the school’s established culture. Through interviews and questions, Dr. Jacobsen learned that for two of the teachers, the new practice did not fit into their belief systems of teaching and learning. One of the teachers had beliefs that aligned with the methods and practices necessary to help students become better problem solvers.

For the teacher with beliefs that were consistent with the new practice, she worked to fully understand what it meant for a student to be a better problem solver and then planned and worked to implement many aspects of the new practice in her classroom. Over the year, she planned and implemented many changes in her classroom practice. She also reported seeing changes that she felt were positive in her students as they became better problem solvers.

For the two teachers with conflicting beliefs to the new practice, there was little change in their understanding of the new practice or how to adopt it. In fact, to avoid a conflict between what they were supposed to do in the new practice and their beliefs, they joined forces and developed their own understanding of how to help their students become better problem solvers. They spent time together and constructed a way to make a different minimal change that was not in conflict with their beliefs. They also reported how they saw their students as being different than the students of the teacher who had success with the new problem solving methods. They used this “difference” to further reinforce their beliefs that the new methods couldn’t work with their students. They did not interact more than necessary with the facilitator, the third teacher, or the principal or vice principal all of whom could have challenged their thinking and given new issues to consider.

How the classroom practices of the three teachers changed or not depended on their beliefs around teaching and learning before the project started. The teacher who had beliefs that aligned with the new practice was able to understand it more deeply and move it into practice. The two teachers who started with beliefs that clashed with the new practice reinforced each other as they minimized how they would implement the new practice. These two teachers also used the “culture” of the school as a basis for defending their position and avoided the facilitator, the third teacher, and the principal and vice principal who were interested in making changes.

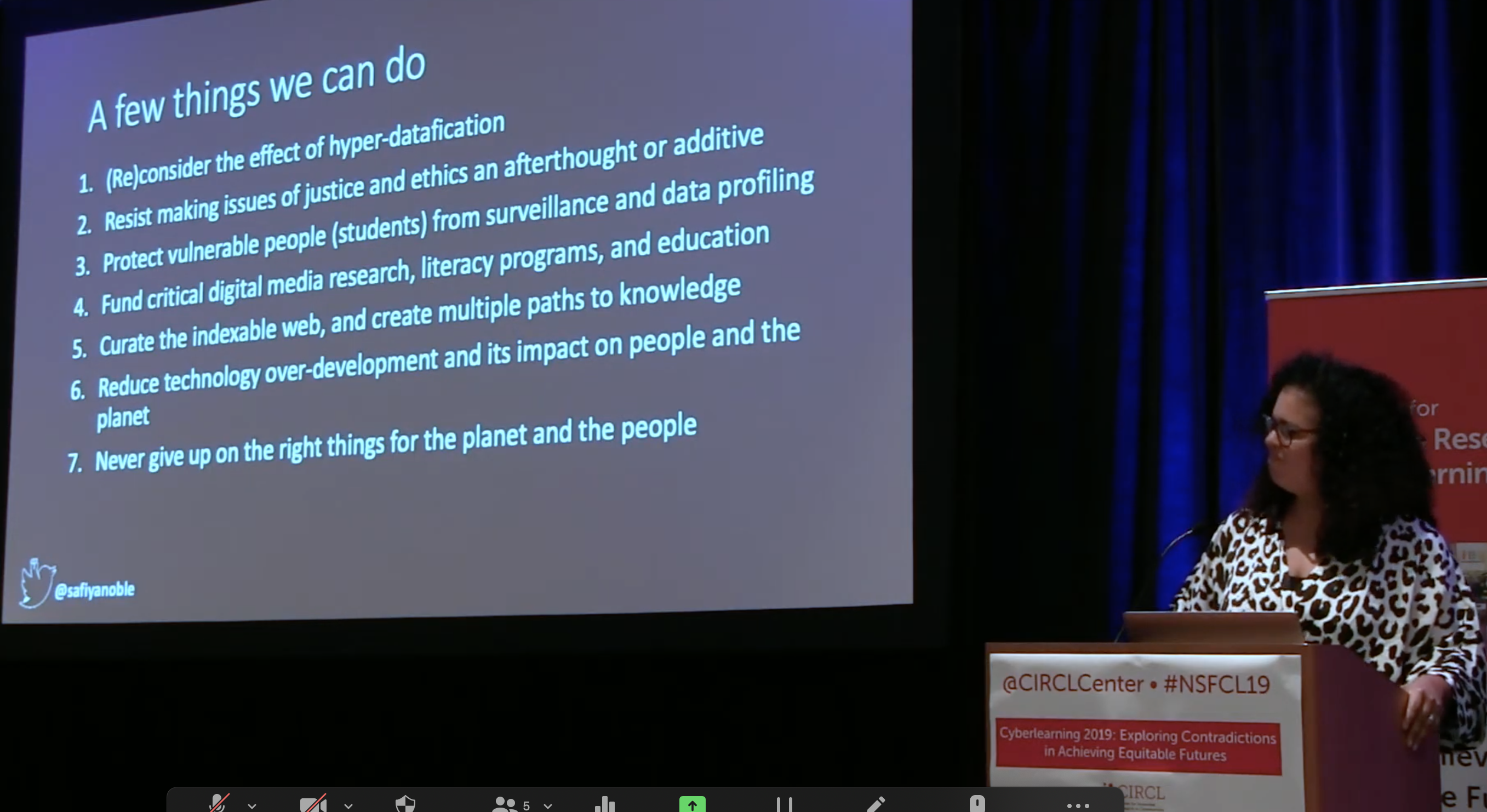

What does all this mean? If teachers are asked to make a change that does not align with what they believe about how students learn, they will most likely change “how they are being asked to change” to a way that matches their beliefs. When teachers are making a change, they need much support to help them understand the change. They need even more support when the change does not align with beliefs. Dr. Jacobsen outlines three strategies to help change teachers beliefs:

1) have them reflect on their beliefs in collaboration with others to think about pedagogical practices,

2) have a peer or coach (gently) challenge their beliefs and give feedback, and

3) give assistance while the teacher is making a change so that they can fully understand what needs to occur.

Additionally, experiencing a new pedagogy as a learner can be very effective. When teachers are put into a situation to be a learner, they can experience and really understand how the pedagogy works to promote learning.

Dr. Jacobsen’s dissertation citation is:

Jacobsen, M. (2019). A Multi-case Study of a Problem-based Learning Approach to Teacher Professional Development (Doctoral dissertation, Pepperdine University).

If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for us, please share via Twitter at @circleducators and #CIRCLedu

Further reading:

Howard, B. C., McGee, S., Schwartz, N., & Purcell, S. (2000). The Experience of Constructivism: Transforming Teacher Epistemology. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(4), 455-465. doi: 10.1080/08886504.2000.1078221

McConnel, T., Eberhardt, J., Parker, J., Stanaway, J., Lundeberg, M., & Koehler, M. (2008). The PBL project for teachers: Using problem-based learning to guide K-12 science teachers’ professional learning. MSTA Journal, 53, 16-21.

Mulford, W., Silins, H., & Leithwood, K. (2004). Problem-Based Learning: A Vehicle for Professional Development of School Leaders. Educational Leadership for Organisational Learning and Improved Student Outcomes, 25-34.

Zhang, M., Lundeberg, M., & Eberhardt, J. (2011). Strategic Facilitation of Problem-Based Discussion for Teacher Professional Development. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 20(3), 342-394. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2011.553258