by Pati Ruiz

This is the second post in a two part series based on my dissertation which focused on encouraging the participation of women and African Americans/Blacks, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native Americans/Alaskan Natives in computing. The first post focused on modeling an interest and passion for CS and creating safe spaces for students. This post focuses on building community, introducing students to careers, and making interdisciplinary connections.

Build Community and Connect Students with Mentors

Family support is important! Young adults encouraged and exposed to CS by their parent(s) are more likely to persist in related careers (Wang et al., 2015). And did you know that women are more likely than men to mention a parent as an influencer in their developing a positive perception of a CS-related field, more often citing fathers than mothers as the influencers (Sonnert, 2009)? Unfortunately, parents’ evaluation of their children’s abilities to pursue CS-related fields differs by gender; parents of boys believe that their children like science more than parents of girls (Bhanot & Jovanovic, 2009). Nevertheless, family support is crucial for young women and supportive family members — whether or not they are connected to the tech world — play a critical role in the encouragement and exposure that young women get to the field.

Helping parents understand the role that they can play is important. As educators, we can model for them how to encourage their children as well as how to dispel misconceptions and harmful stereotypes that their children might have heard. Sometimes parents and family members themselves might unknowingly be perpetuating harmful computer science world misconceptions with the comments they make to their children. As teachers, we can provide parents with training that might help them understand how to encourage and expose their children to the field in positive ways. After all, the research shows that this support can be provided by anyone – not just educators.

All of the young women in my study described the value of mentors. Even seeing representations of female role models in the media can encourage a young woman to pursue a CS-related degree. It’s important for young women to see representations of people who look like them in the field and to have real-life female mentors and peers who can support them in their pursuit of CS-related degrees and careers. As a result of the low number of women in the field, mentors and role models for women are primarily men. While this can be problematic, it does not have to be. Cheryan et al. (2011) found that female and male mentors or role models in computing can help boost women’s perceived ability to be successful if those role models are not perceived to conform to male-centered CS stereotypes. The gender of the role model, then, is less important than the extent to which that role model embodies current STEM stereotypes.

The actionability of some of the factors described above, then, allows educators and others to positively influence and encourage young women in high school to pursue CS degrees in college (Wang et al., 2015).

Introduce Careers

In their recent report titled Altering the Vision of Who Can Succeed in Computing, Couragion and Oracle Academy described the importance of introducing youth to careers in technology. They find that:

“It is critical to improve the awareness and perception of a breadth of careers in computing to meet the demands of our workforce and the desires of our students. We need to elevate high demand and high growth computing fields such as user experience (UX) and data science – that when understood, appeal to and attract underrepresented populations.“

What this report found is what I found in my research; many African Americans/Blacks, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native Americans/Alaskan Natives students don’t know people working in the computing field and don’t know what career options can look like. Couragion is working to change this by providing inclusive, work-based learning experiences that prepare students for jobs of the future. What I like about Couragion’s approach is that students are able to use an app to explore careers and engage with role models through text, activities, and videos. As they work their way through different career options, students take notes and reflect using a digital portfolio. I think this is a great way for students to develop career consciousness, something I wish I had when I was in school (as a student and teacher)!

As a teacher, the way I would connect my students with industry careers was to connect with local groups like GirlDevelopIt and invite speakers to my classroom. I also had college students visit my classroom – it usually works well to have recent graduates come back to talk to students because students relate well to recent high school graduates. I also introduced computer scientists in the news. If I were teaching right now, I would highlight 2018 MacArthur Fellow Deborah Estrin. In her Small Data Lab at Cornell, Dr. Estrin and her team are designing open-source applications and platforms that leverage mobile devices to address socio-technological challenges in the healthcare field. Or, I might direct them to this recent article written by Clive Thompson titled The Secret History of Women in Coding.

Some participants in my study mentioned that they ended up majoring in CS because of a mentor. One participant talked about how one of her high school teachers “dragged her to” a Technovation event. There, she ended up seeing a young woman who she “saw herself” in so she decided to apply to the same college that the mentor attended, got in, and went. This participant envisioned herself there because of this near-peer. She said that she didn’t connect with her mentor once she got to the university that they both attended for a year together, but just seeing her ahead of her in the program was motivating.

Again, the idea here is to create opportunities for students to connect with people in the field – to see themselves and to see the possibilities. Some groups that my students have worked with include Girls Who Code, Black Girls Code and Technolochicas – there are many others. Which ones do your students work with?

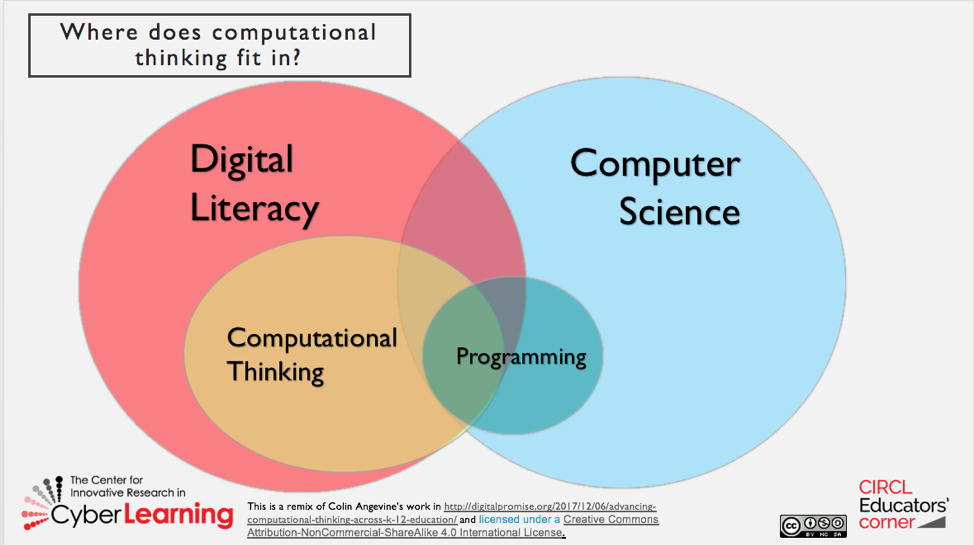

Make Interdisciplinary Connections

Finally, we have the idea of making interdisciplinary connections. CIRCL Educator Angie Kalthoff wrote a post for EdSurge discussing this very topic. Angie encourages teachers to ask their students: What are you doing outside of school that you want to tell other students about? She and a group of Minnesota educators organize student-powered conferences where middle schoolers showcase what they’re really interested in learning about. Check out her post because getting together with other educators to organize your own student-powered conference might be an excellent way you support and recruit young women and African Americans/Blacks, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native Americans/Alaskan Natives!

Interdisciplinary connections can be facilitated by teachers and it’s important to note that all of my study participants were very thankful to their K-12 teachers for having encouraged their pursuit of a technical field – even if they didn’t know they had. As one participant described, “a teacher who’s clearly passionate” is particularly encouraging.

One resource that can help you make interdisciplinary connections with students iss Connected Code: Why Children Need to Learn Programming by Yasmin B. Kafai and Quinn Burke. Join the CIRCL Educators book club to discuss this book starting in April!

Please note that the featured image for this post was created by #WOCinTech Chat, check them out! We’d love to hear from you — Tweet to @CIRCLEducators or use #CIRCLEdu.