by Marlon Matilla

The Navigating Ethical Al: Interactive Lessons and Equitable Practices for Educators webinar serves as a microcosm of the broader challenges and opportunities that artificial intelligence (AI) presents in the educational landscape. The session brought together educators to explore the ethical implications of integrating AI into classrooms, highlighting the intersection between technological innovation and pedagogical responsibility.

The Ethical Imperative in AI Education

Central to the discussion was the need for educators to critically engage with AI, not just as a tool but as a complex system with far-reaching implications. Dr. Kip Glazer, principal at Mountain View High School, emphasized that understanding the technical distinctions between different types of AI—such as generative and supervised AI—is crucial for educators (see Ethical Use of AI – Privileging measured and deliberate thinking, for further thoughts from Dr. Glazer). This technical literacy forms the foundation for ethical decision-making, as educators must navigate the biases inherent in AI systems and their potential impact on students and teaching practices. The dialogue in the session reflects a growing recognition that AI’s role in education is not neutral; it is laden with ethical considerations that educators must address proactively.

Practical Engagement with AI Ethics

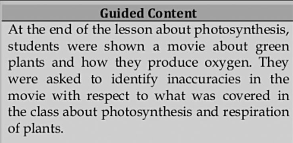

Assistant professor Dr. Victoria Delaney introduced the Stanford Classroom-Ready Resources About AI for Teaching (CRAFT) project, which exemplifies how these ethical considerations can be translated into classroom practice. By developing adaptable AI literacy resources, the CRAFT initiative seeks to empower teachers to integrate AI education in a way that is both practical and responsive to the needs of diverse student populations. The project underscores the importance of flexibility and customization in educational resources, recognizing that teachers must be able to tailor AI lessons to their specific classroom contexts.

This approach is further exemplified by my CRAFT Ethical Engine card game, a tool I designed to foster critical thinking and ethical reasoning among students. This game moves beyond theoretical discussions, offering a hands-on way for students to grapple with the real-world implications of AI. Through scenarios like AI in law enforcement or AI-controlled military drones, the game prompts students to consider both the benefits and risks of AI technologies, thereby cultivating a more nuanced understanding of AI ethics.

Collective Responsibility and Advocacy

The session also highlighted the collective responsibility of educators to advocate for ethical AI practices. The Educator Bill of Rights, discussed by Dr. Kip Glazer, is a testament to this advocacy. It asserts the rights of educators to have a say in the AI tools introduced into their work environments and emphasizes the need for transparency and equity in AI implementation. This document not only empowers educators to protect their professional autonomy but also ensures that AI adoption in schools does not exacerbate existing inequalities or undermine educational goals.

The session’s exploration of these themes reflects a broader narrative within education: the need for a critical, reflective approach to technology. As AI becomes increasingly integrated into classrooms, educators are not just passive recipients of these tools; they are active participants in shaping how AI is used and understood in educational settings. This requires a deep engagement with the ethical dimensions of AI, as well as a commitment to advocating for practices that are fair, transparent, and aligned with educational values.

Engaging Educators in Discussion

The CRAFT Ethical Engine card game resource presented in the session and the Educator Bill of Rights can serve as starting points for bringing educators and students into conversations about ethical issues. As the presenters emphasized in this webinar, it is important to empower educators to think critically about how to safeguard against the ethical pitfalls that these technologies can produce and bring awareness to students about potential issues.

A Unified Perspective on AI in Education

Synthesizing the insights from the session reveals a unified perspective on the role of AI in education: It is a powerful tool that holds both promise and peril. The session participants collectively underscore that the successful integration of AI into education hinges on the ability of educators to critically assess and ethically navigate these technologies. Furthermore, our conversations with educators illustrate the necessity of an ethical framework for AI in education, one that is informed by a deep understanding of the technology and a commitment to equity and fairness. It is my hope that this synthesis of ideas and the resources shared can provide guidance for educators who are navigating the complex landscape of AI. Educators need more resources to ensure they are equipped to make informed, ethical decisions that benefit both their students and the broader educational community.

About the Author

Marlon Matilla is an educator dedicated to advancing data-driven and technology-focused learning in K-12 STEM education. Since 2015, he has taught mathematics, computer science, and cybersecurity with a strong emphasis on hands-on learning. As a CIRCLS Educator Fellow, he has contributed to AI education initiatives, including the co-design of ethical AI resources through Stanford’s CRAFT Fellowship. His recent publication, Optimizing Breakfast Choices: Leveraging Data Analytics in Packaged Foods for Informed Student Nutrition Decisions, supported by the University of Arkansas’ NSF-funded Data Analytics Teacher Alliance RET program, is published in the ASEE Professional Engineering Education Repository. Committed to merging research with practice, Marlon (aka Matt) aims to continue as a researcher-educator, fostering data literacy and ethical AI technology use in education.